Referral Notes:

- People with epilepsy have a markedly higher risk of mood and behavioral disorders than the general population.

- Double boarding in psychiatry and neurology is advantageous in managing the disease’s complex psychiatric comorbidities.

- Developing a nuanced analysis of each patient’s case is crucial to symptom management, and to mitigating epilepsy’s psychosocial impacts.

One in three people with epilepsy (PWE) will suffer from a psychiatric disorder during their lifetime—a risk two to five times higher than in the general population. This vulnerability stems from an array of neurological and psychosocial factors, often acting in combination. Medication side effects can play a role as well.

Given this complexity, dual training in psychiatry and neurology offers a distinct advantage. NYU Langone Health is one of just four centers in the United States to offer such preparation. All residents in the Neurology and Psychiatry Residency Training Program rotate through NYU Langone’s Comprehensive Epilepsy Center.

Several program graduates now serve on the Department of Psychiatry faculty, often treating PWE referred by neurologists or epileptologists. “Our training not only gives us the knowledge to make challenging clinical decisions, but helps us show patients that their experiences aren’t random and inexplicable,” says Deepti Anbarasan, MD, who completed her dual residency in 2015 and has an additional board certification in epilepsy.

“Our training not only gives us the knowledge to make challenging clinical decisions, but helps us show patients that their experiences aren’t random and inexplicable.”

Deepti Anbarasan, MD

Together, Dr. Anbarasan and colleague Scott E. Hirsch, MD, a 2007 alumnus with expertise in epilepsy, are helping to shape NYU Langone’s approach to treating psychiatric comorbidities of the disease.

Delving into Depression

The most common mood disorder associated with epilepsy is depression. A 2004 CDC study found that 32.6 percent of PWE reported feelings of depression, compared to 15.5 percent of those without. “For individuals with epilepsy, depression is the biggest factor that decreases quality of life,” Dr. Anbarasan says. “So it’s critical that we address even low-grade depressive symptoms in our patients.”

Such symptoms may be driven partly by the life-altering aspects of epilepsy. “Patients often aren’t allowed to drive,” notes Dr. Hirsch. “Some can’t even bathe alone. They lose their independence.”

Seizures themselves can also trigger mood changes, as can the neurological anomalies that underly the disease. In addition, some antiepileptic drugs (AED), such as levetiracetam and the GABAergic medications, are associated with an increased risk of depression.

Fortunately, several AEDs have antidepressant properties, including lamotrigine, divalproex sodium, and carbamazepine. Conventional antidepressants, particularly SSRIs such as sertraline and escitalopram, can also be safely used in PWE. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has demonstrated efficacy as well.

Addressing Anxiety

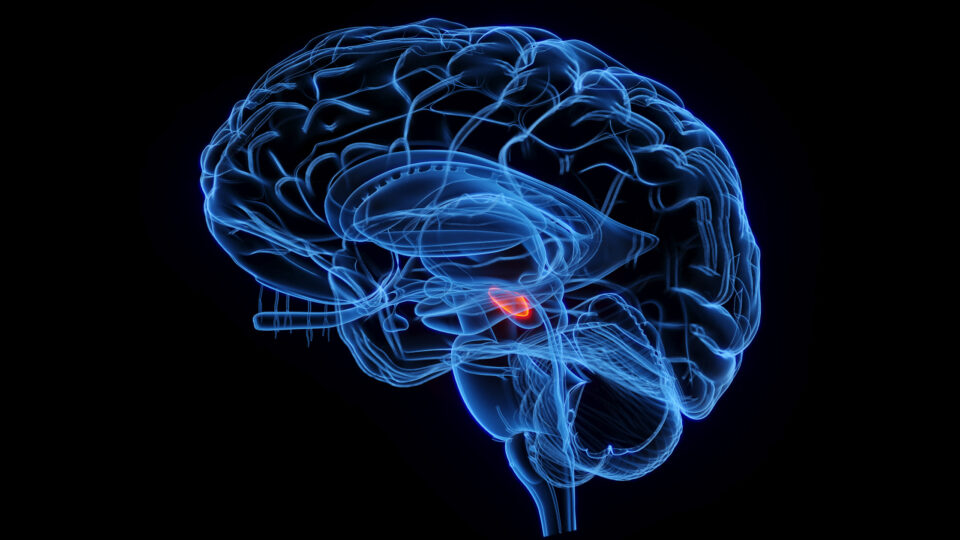

Anxiety disorders are also highly prevalent among PWE, affecting at least 28 percent of patients compared to 19 percent of those without epilepsy. Again, the trouble may arise from errant brain circuitry as well as psychosocial factors. “For example, the temporal lobe is implicated in anxiety,” says Dr. Anbarasan. “If someone has temporal lobe epilepsy, it stands to reason that they may be more prone to anxiety as well.”

To treat anxiety in PWE, she stresses, it is crucial to determine the etiology of the symptoms. Seizures can sometimes be mistaken for panic attacks, and panic attacks for seizures. Anxiety can also be a component of preictal auras, or of epilepsy-related psychoses. And it can simply be a psychological response to the uncertainties and dangers of the disease itself. “Clinical tests, such as EEGs and MRIs, can help us get a clearer picture of what’s happening,” Dr. Anbarasan says.

In many cases, SSRIs as well as CBT and other psychotherapies can be helpful for epilepsy-related anxiety. Some AEDs—particularly pregabalin, carbamazepine, and valproate—also have anxiolytic properties. Benzodiazepines are effective for acute anxiety in PWE, but due to potential side effects including dependence, “caution should always be exercised in prescribing these drugs,” she advises.

Paying Attention to ADHD

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is another common comorbidity in PWE, affecting an estimated 20 percent of patients compared to 6 percent of the general population.

“We tend to undertreat ADHD because of a concern about using stimulants, which theoretically carry the risk of lowering seizure threshold,” Dr. Anbarasan observes. “But when used at appropriate dosages in patients with well-controlled epilepsy, it can be life-changing.”

Interpreting Psychosis

The prevalence of psychotic disorders among PWE is estimated to be as high as 9.2 percent, versus just over 3 percent in the general population. Although the numbers are smaller than for other psychiatric comorbidities, the impact on patients and their loved ones can be enormous.

“Typically, [epilepsy-related] psychoses respond to antipsychotic drugs, but the latter must be titrated to avoid increasing the risk of seizures.”

Scott E. Hirsch, MD

The complexities of diagnosis and treatment are formidable as well. “As with depression or anxiety, the first challenge is figuring out whether a psychosis is due to epilepsy, would have occurred independently, or is a side effect of the medication,” Dr. Anbarasan explains.

To determine whether a psychotic episode was triggered by a patient’s epilepsy, Dr. Anbarasan first scrutinizes the timeline in relation to seizures and the symptoms. “Postictal psychosis is often associated with refractory epilepsy, and with religious and persecutory themes,” she says. “Interictal psychosis usually arises later in life than, say, schizophrenia, and its symptoms tend to be lower-grade.”

“Typically, these psychoses respond to antipsychotic drugs, but the latter must be titrated to avoid increasing the risk of seizures,” adds Dr. Hirsch. “You can use the EEG to guide you, and slow down if you see epileptiform activity increasing.”

Helping Patients Regain a Sense of Control

If a psychosis doesn’t fit standard models or resolve with antipsychotics, the patient’s AED may be responsible; switching drugs may be necessary. (Studies suggest that levetiracetam and several other antiepileptics can increase the risk of psychosis, though the incidence is low.) Another potential trigger is forced normalization, a poorly understood phenomenon in which suppressing seizures elicits psychiatric disturbances. In some cases, reducing AED dosage can alleviate the problem.

This kind of nuanced analysis of each patient’s case, Dr. Anbarasan observes, is key not only to symptom management but also to mitigating epilepsy’s psychosocial toll. “The nature of this condition is that patients feel a loss of control, which can be very scary,” she says. “To give them a sense of agency, I think, is crucial.”