A Multi-Tiered Approach Unmasks an Elusive Disorder

A woman in her 60s was referred to Kiril Kiprovski, MD, a clinical associate professor of neurology, with severe stiffness and spasticity in her lower extremities. Her symptoms had first appeared 6 years earlier, she reported, and all treatments had been ineffective.

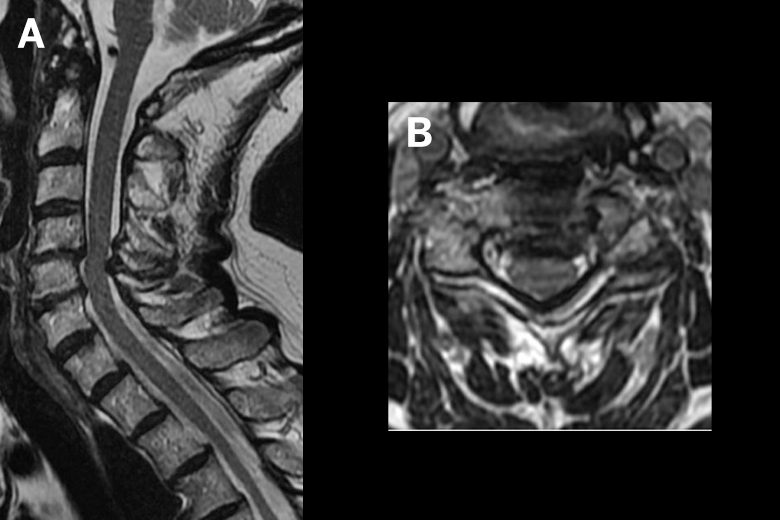

A spine surgeon had diagnosed the patient with spinal stenosis and performed two decompression surgeries. Later, an orthopedic surgeon had performed tendon lengthening and decompression of the peroneal nerve in the left leg. Still, the woman remained unable to walk more than a few steps without stumbling.

“This woman’s life was terribly limited by her illness. She’s excited about being able to do more.”

Kiril Kiprovski, MD

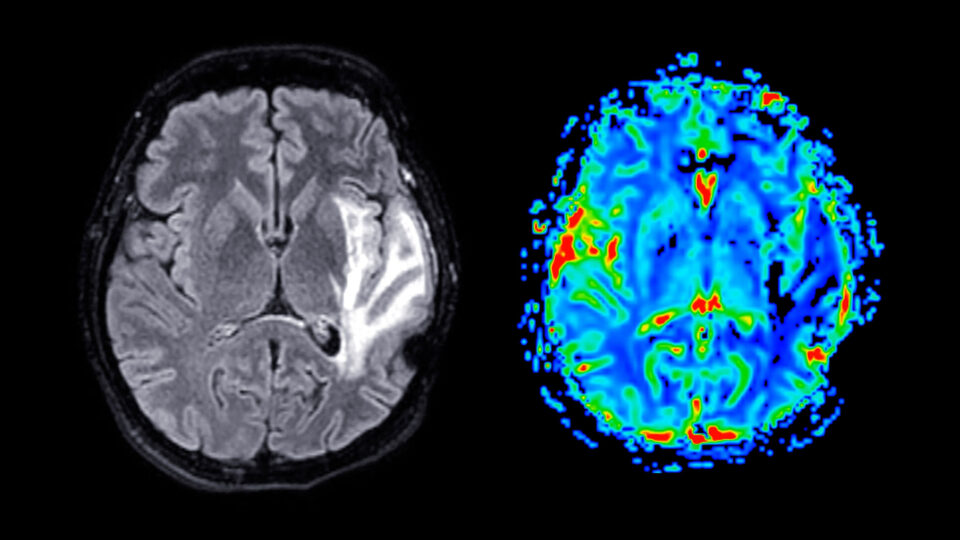

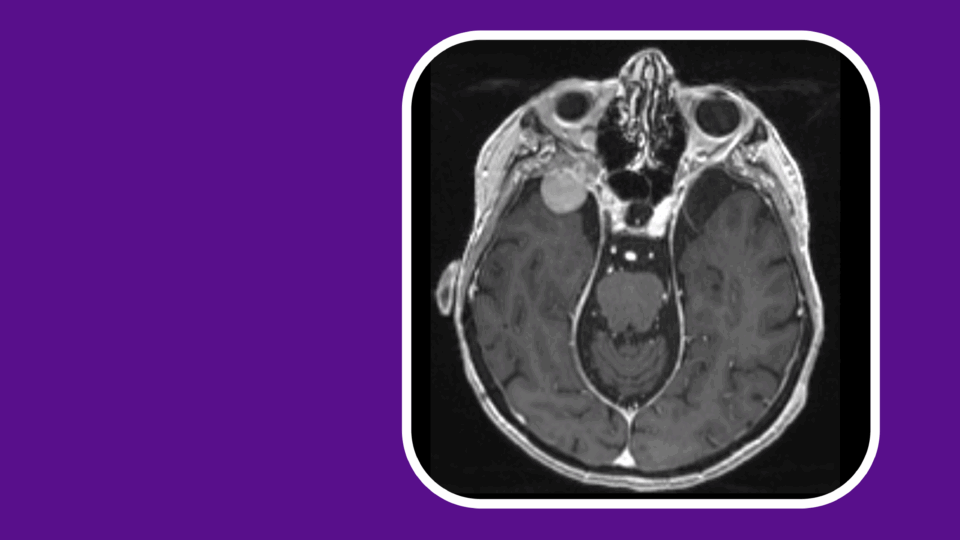

At NYU Langone Health, Dr. Kripovski inspected the patient’s MRIs and saw no significant compression of the spinal cord. A physical exam, however, led the neurologist to suspect stiff-person syndrome (SPS)—a rare, progressive autoimmune disorder that affects 1 to 2 out of every million people.

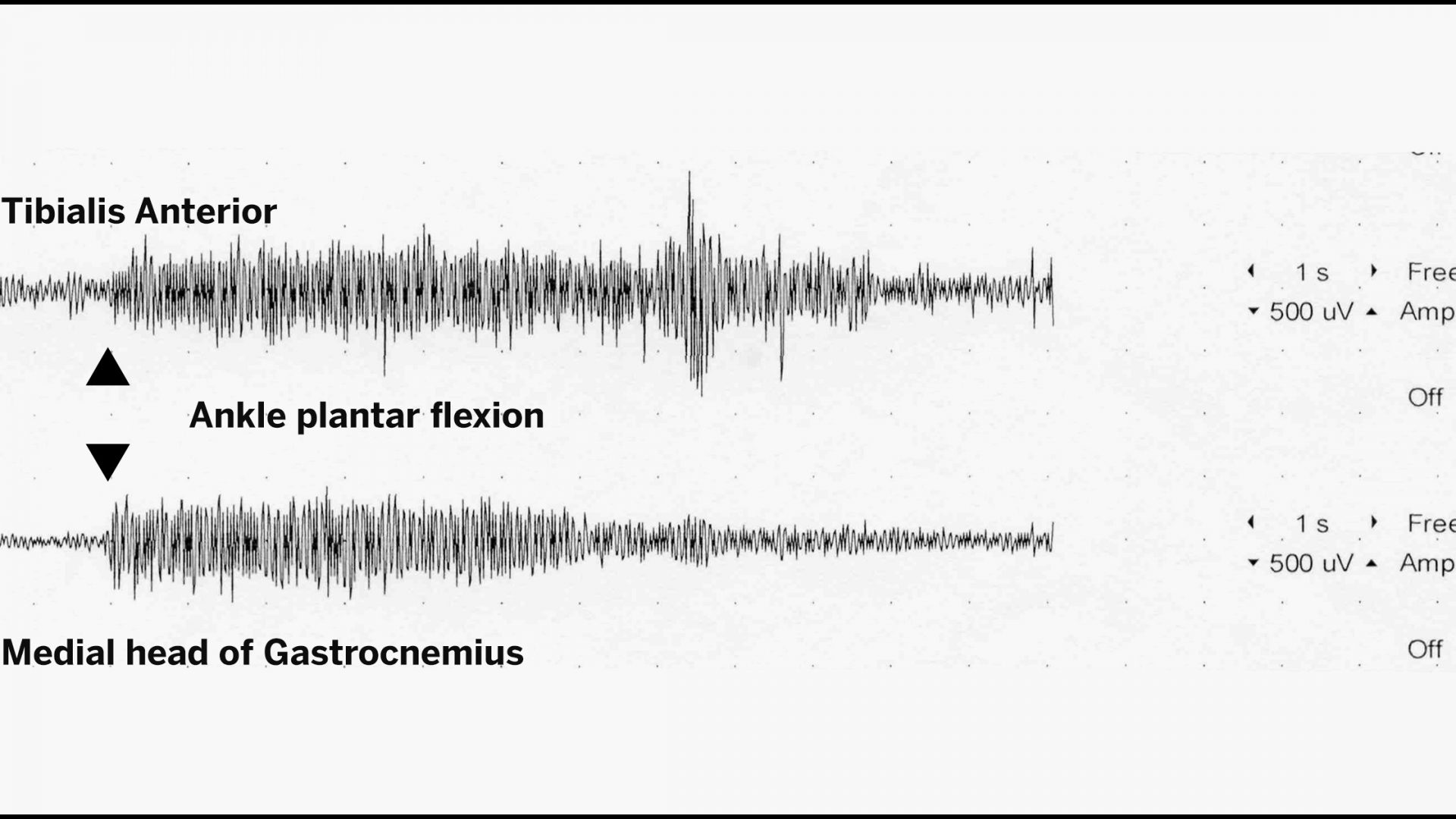

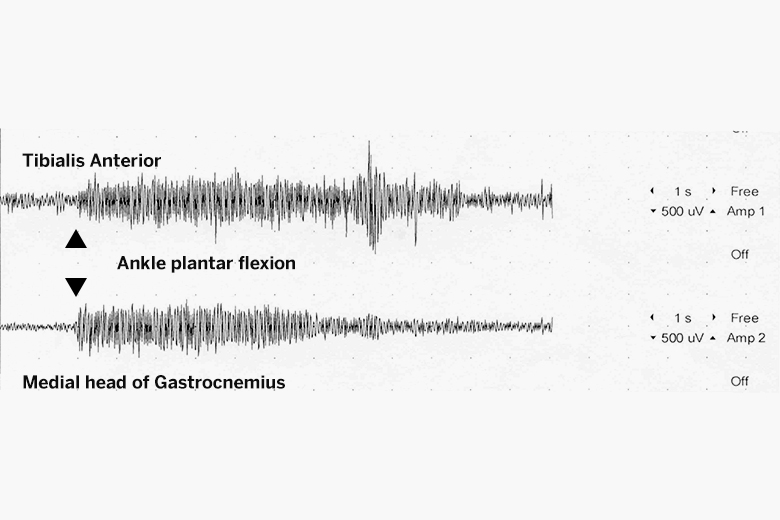

The symptoms of SPS arise from the disruption of central nervous system pathways that normally inhibit muscle contractions. “Instead of the agonist muscle contracting and the antagonist relaxing, both muscles are activated at the same time,” Dr. Kiprovski explains.

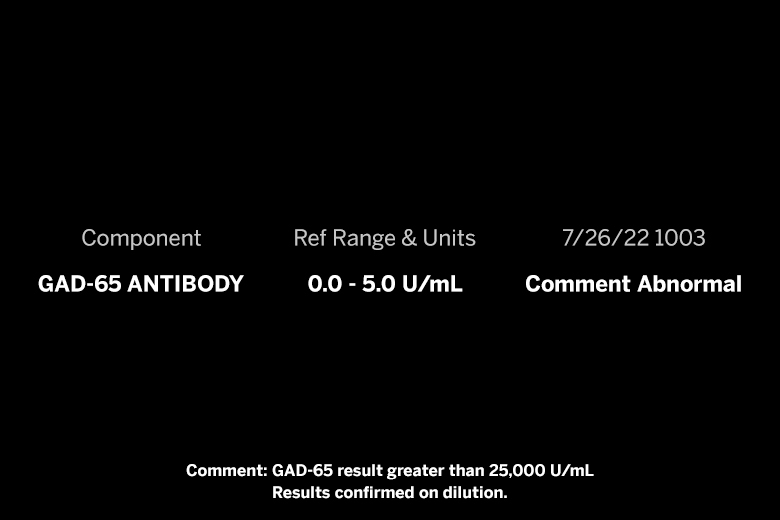

Although the syndrome’s etiology is uncertain, it is usually accompanied by elevated levels of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) antibodies. However, anti-GAD antibodies can also be associated with autoimmune diabetes mellitus.

To confirm his clinical impression, Dr. Kripovski ordered bloodwork and performed surface electromyography, both of which showed concerning signs of SPS.

After completing the diagnosis, he prescribed clonazepam, a standard treatment. Within weeks, the woman’s mobility increased significantly. In hopes of improving it further, she was recently started on intravenous immunoglobulin, which has been shown to reduce symptoms in some patients.

“This woman’s life was terribly limited by her illness,” Dr. Kiprovski says. “She’s excited about being able to do more. Her whole family’s excited about it. And, of course, I’m excited, too.”