More than two decades after the attack on the World Trade Center (WTC) on September 11, 2001, many first responders and survivors continue to experience health impacts from their exposure to toxic conditions.

From the beginning, NYU Langone Health, in collaboration with NYC Health + Hospitals, has been an integral player in the care and surveillance of these patients.

In 2010, following the establishment of the James Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act, NYU Langone began providing care as part of the CDC’s WTC Health Program. This encompasses the WTC Health Program Clinical Center of Excellence at NYU Langone for responders, directed by Denise J. Harrison, MD, and the WTC Environmental Health Center at NYC Health + Hospitals for survivors, directed by Joan Reibman, MD.

Both Dr. Harrison and Dr. Reibman were caring for patients when the attacks occurred.

“The community has always been the key driver of our agenda.”

Denise J. Harrison, MD

“Right away we started seeing patients in the clinics and developing specialized treatment for responders, survivors, and residents,” Dr. Harrison says.

Care for Responders

Shortly following the WTC disaster, Dr. Harrison received funding from the Robin Hood Foundation to travel to affected communities to screen and refer day laborers who played a vital part in the recovery effort but would otherwise not have access to care. “The community has always been the key driver of our agenda,” Dr. Harrison says.

She emphasizes that the leadership within NYU Langone’s WTC Health Program meets regularly with community organizations and union members who share in the decision-making involving research and patient care.

As a result, what began as a screening program for responders now provides comprehensive services for health monitoring, medical treatment, mental health, pharmacy, and benefits counseling. If a responder is approved, the program pays for all their medical expenses.

Treating Community Survivors

While NYU Langone’s WTC Health Program treats a broad range of responders, from firefighters to healthcare personnel to iron workers, the WTC Environmental Health Center assesses and treats WTC-related physical and mental health conditions of survivors—eligible residents, students, workers, or passersby in the area on 9/11.

In 2005, Dr. Reibman and colleagues published an epidemiologic survey of over 2,300 individuals who lived and worked in the WTC geographic area on or after 9/11. The study showed that a significant number had developed respiratory issues.

By 2008, the WTC Environmental Health Center had received federal funding to provide treatment for these survivors.

“Our goal is to provide care for all those with conditions resulting from dust and fume exposures, but also to provide surveillance of new conditions.”

Joan Reibman, MD

Notably, Dr. Reibman says, the WTC Environmental Health Center was included as the only Center of Excellence for survivors under the CDC’s WTC Health Program and serves as a model for subsequent survivor programs. To date, there are over 14,000 survivors enrolled in the WTC Environmental Health Center.

“These patients continue to inform us about WTC-related illnesses,” Dr. Reibman says. In 2022, her team detailed how WTC-related airway injury impacts chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

“Our goal is to provide care for all those with conditions resulting from dust and fume exposures, but also to provide surveillance of new conditions.”

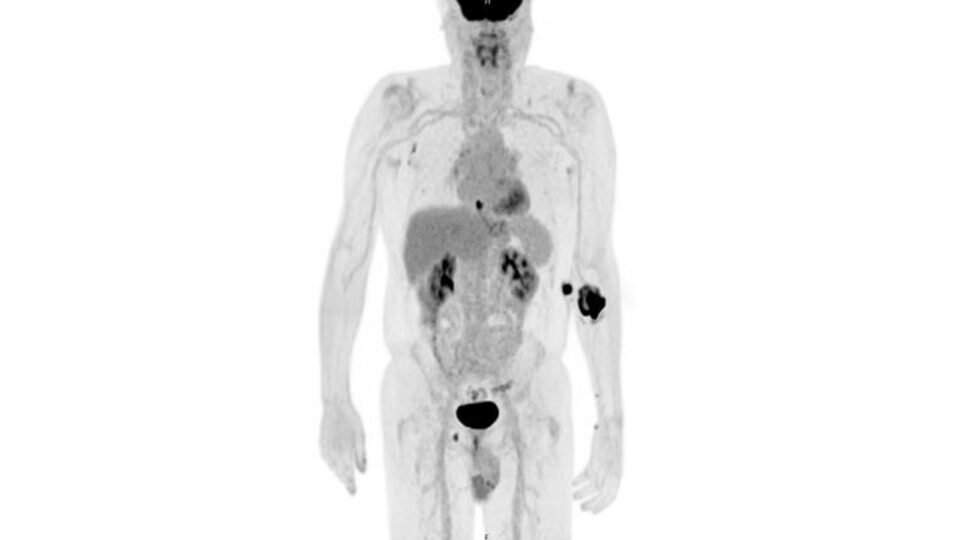

Cancer Characteristics

Much of these surveillance efforts are directed at cancers. Where a majority of responders seeking treatment have been men, and Dr. Harrison’s research has focused on these patients, the survivor group comprises about 50 percent women. “Surprisingly, many of these women have had breast cancer rather than lung cancer,” Dr. Reibman notes.

The survivor cohort is diverse ethnically and socioeconomically, and about 50 percent had acute exposure (to the dust clouds) and others had chronic exposure (lived or worked in the area).

“This focus on the community exposed to the WTC disaster is important because it allows us to study environmental exposures and look at the characteristics of cancers,” Dr. Reibman says. “We aim to understand the commonalities and differences among the cancers, and to use the unique longitudinal data to better understand environmental exposures and cancer in general.”

This effort has led to the establishment of a pan-cancer database. “We’re looking to collaborate with other researchers studying cancers: we have groups focused on lung cancer, melanoma, and breast cancer. We also hope to recruit people who were children or youth on 9/11 to study how they’ve been impacted,” Dr. Reibman says.

The federal WTC Health Program is still accepting both responder and survivor enrollees. “For anyone who had exposure but never sought treatment or has more recently developed health issues, it’s not too late to enroll in the program,” Dr. Harrison says. “We advocate for everyone coming in.”