During the global mpox outbreak that began in 2022, NYU Langone Health ophthalmologists at Tisch Hospital and NYC Health + Hospitals/Bellevue cared for two patients whose advanced immunosuppression due to prior HIV infection led to previously unreported and unusually severe oculocutaneous manifestations.

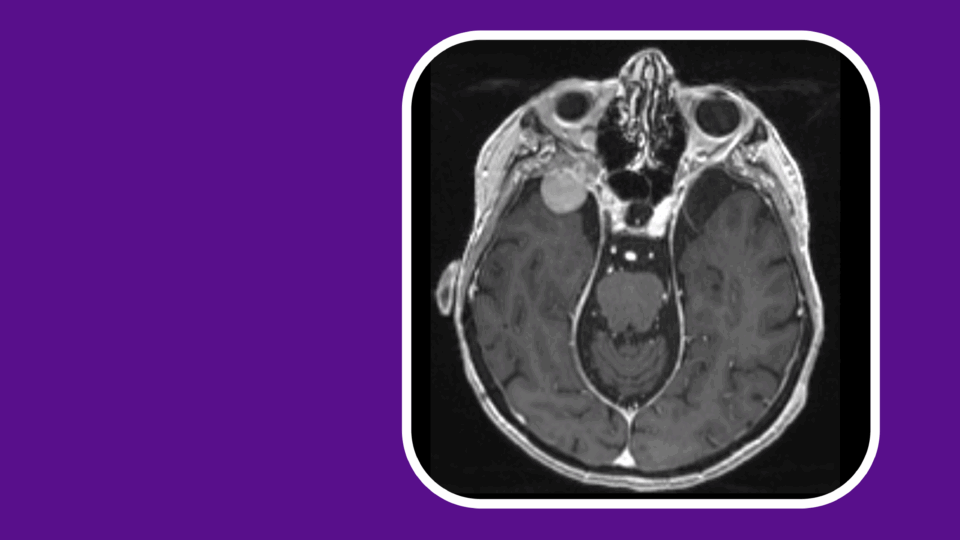

In a study published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases, the clinicians reported that both patients with mpox infection developed severe lesions that spread to a confluent panfacial gangrene with skin necrosis around the eyes and eyelids. In one case, the gangrene caused bilateral globe compromise from corneal perforations.

Despite intensive care, both patients died due to systemic complications from their treatment-resistant infections.

“Our conclusion is that in patients with advanced cell-mediated immunodeficiencies like HIV/AIDS, confluent necrosis can develop from an initial mpox lesion.”

Steven Carrubba, MD

Based on careful histology and a review of decades-old case reports, the researchers found a striking similarity to symptoms of severe infection from the closely related vaccinia virus.

“The big takeaway is that we can learn a lot about this disease from prior experiences with related orthopoxviruses that are genetically and clinically similar, such as smallpox and vaccinia,” says chief ophthalmology resident Steven Carrubba, MD, the study’s lead author.

A Rare Progression

Classic mpox symptoms often include a skin rash or painful lesions, while ophthalmic manifestations can include a vesicular rash around the eyes and eyelids, conjunctivitis, and blepharitis—and in more serious cases, corneal infection and scarring.

Ophthalmology chair Kathryn A. Colby, MD, PhD, who advised on the study, notes that mpox has the potential to be very severe in patients with undiagnosed or untreated immunosuppression, and that an immunological work-up should be considered in anyone presenting with the disease.

“This study underscores the importance of paying attention to previously published literature, even if it is from the distant past.”

Kathryn A. Colby, MD, PhD

“This study underscores the importance of paying attention to previously published literature, even if it is from the distant past, when faced with new conditions or infectious diseases,” Dr. Colby says.

“Through clinical analogy, we can anticipate which systemic and ophthalmic complications of mpox may arise in people who are immunocompromised, and what to expect during future outbreaks,” Dr. Carrubba adds.

Lessons from History

In very rare cases, according to historical reports, patients vaccinated against smallpox with a replicative form of the vaccinia virus developed profound cutaneous gangrene at the site of inoculation and subsequently throughout the body.

In this “progressive vaccinia,” patients were unable to mount a lymphocyte-driven, cell-mediated skin response, which allowed the virus to spread and cause highly necrotic gangrenous lesions.

Tellingly, that cutaneous gangrene occurred predominantly in patients with immunodeficiencies involving T cells, such as severe combined immunodeficiency, lymphoma, and leukemia.

“Histologically and clinically, we saw almost the exact same findings in patients with advanced AIDS who became coinfected with mpox,” Dr. Carrubba says, including an almost complete lack of lymphocytes in the affected tissues.

“Our conclusion is that in patients who have advanced cell-mediated immunodeficiencies like HIV/AIDS, confluent progressive necrosis can develop from an initial mpox lesion by uninhibited and contiguous spread of virus in tissues devoid of functional lymphocytes,” Dr. Carrubba says.

“One lesion continues to expand because the immune system is not able to contain it, much like what clinicians saw with the vaccinia virus.”

The similarities between progressive cutaneous mpox and progressive vaccinia also provide insight into how mpox corneal lesions may evolve after autoinoculation of an immune-deficient ocular surface, potentially explaining cases of necrotizing keratitis and globe compromise.

Treatment Considerations

Neither mpox patient had been vaccinated before the onset of symptoms nor had they been taking highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) to treat their advanced AIDS.

“For any immunosuppressed patient who presents with suspected mpox, even before official diagnosis, starting treatment early is key,” Dr. Carrubba says. The antiviral tecovirimat is the mainstay systemic treatment for mpox.

In addition, he says, starting patients on HAART is critical for immune reconstitution, while a non-replicative mpox vaccine can be given within 14 days of suspected exposure, before symptom onset.

For severe or treatment-resistant cases, the CDC recommends additional therapeutics such as cidofovir, brincidofovir, or vaccinia immune globulin.

For patients with active skin lesions, maintaining good hand hygiene and avoiding contact lenses are important precautions against localized autoinoculation of the eyes, Dr. Carrubba adds. Trifluridine antiviral eyedrops can be used both prophylactically and as a treatment for corneal and conjunctival disease, while antibiotic and lubricating eyedrops can prevent bacterial superinfection and corneal desiccation.

Based on similarities between mpox and vaccinia, Dr. Carrubba says, the population at risk for progressive cutaneous or ophthalmic mpox extends beyond patients with HIV/AIDS to include people with hematologic malignancies, such as leukemia and lymphoma, and other diseases that compromise host lymphocyte function.

“It’s important for patients and clinicians to maintain awareness that such severe disease can occur in immunocompromised populations so that both parties can seek the right preventive and treatment measures,” he says.