Encrusted pyelitis (EP) and cystitis is a rare but increasingly reported condition linked to urea-splitting bacteria, most notably Corynebacterium urealyticum (CU). The condition is often overlooked and can be life-threatening. CU, a commensal skin organism, is particularly associated with infections in immunocompromised individuals and those with a history of endoscopic urological interventions; however, infections can also manifest in otherwise healthy individuals.1

Symptoms resulting from CU infections range from asymptomatic bacteriuria (noted in 0.2 percent of urine cultures) to urologic sepsis upon the progression to EP. Various local and systemic manifestations related to urothelial calcification may occur, with urinary obstruction and calcified pyelitis being the most prevalent. These complications often result from the detachment of calcifications, the formation of urolithiasis, and ureteral obstruction, which can precipitate acute renal failure.2

This report outlines the case of a 60-year-old male diagnosed with recurring bilateral urolithiasis and left-sided non-obstructive pyelonephritis, who subsequently developed secondary septic shock necessitating temporary hemodialysis. Notwithstanding the extensive EP, the patient achieved a successful outcome with oral urinary acidification and antibiotic therapy.3

This case highlights how complete resolution of EP may be attainable without recourse to invasive interventions or unnecessary manipulations of the urinary tract.

Case Highlights:

- A 60-year-old male with a history of recurrent bilateral urolithiasis, left non-obstructive pyelonephritis, and septic shock requiring temporary hemodialysis presented for care.

- Initial evaluations revealed sterile pyuria, urinary pH of 8, and urothelial mucosa calcification evident on CT. A definitive diagnosis of EP alongside a CU infection was established through prolonged urine culture (>48 hours) utilizing blood agar in enriched CO2 conditions.

- The CU infection was managed with oral linezolid, while the encrustations were treated through ureteral stenting combined with oral acidification using acetohydroxamic acid.

- After one year of oral acidification with L-methionine, the encrustations were successfully treated.

Patient Case

The patient had a history of dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia and was previously diagnosed at another facility with bilateral nephrolithiasis following an episode of left non-obstructive pyelonephritis that resulted in secondary septic shock.

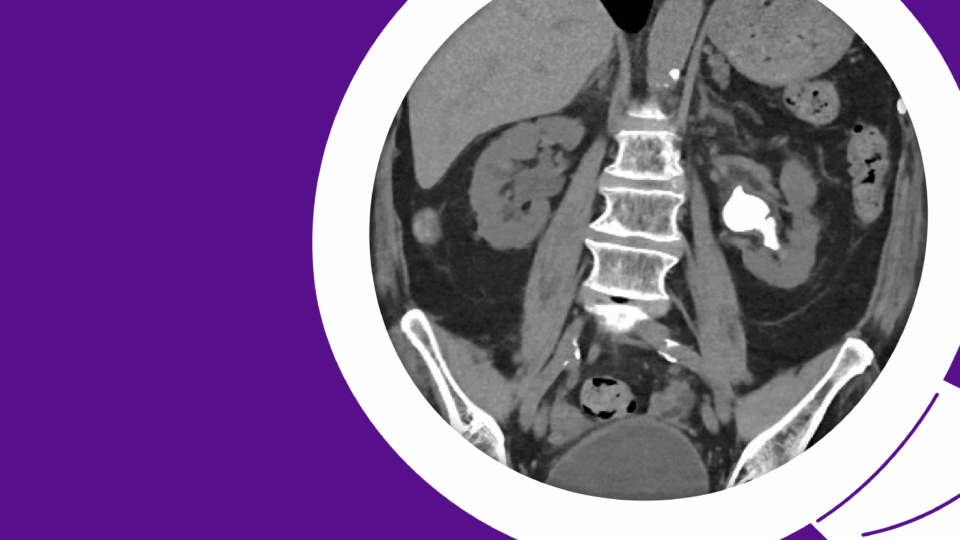

After a two-year period marked by increasing stone burden, he was referred for definitive intervention. A CT scan revealed a 2 cm stone in the right kidney, alongside left renal atrophy. A radioisotope renography demonstrated differential renal function, with the right kidney exhibiting 84 percent and the left only 16 percent. His baseline creatinine level was recorded at 2.83 mg/dL (250 μmol/L).

During his referral period, the patient presented to the emergency department with severe dysuria and fever, reaching 101ºF. Although physical examinations returned normal results, he exhibited highly viscous urine with mucus debris. Urinalysis indicated sterile pyuria and a urinary pH of 8. Further blood tests revealed acute renal insufficiency, reflected by creatinine levels of 6.72 mg/dL (594 μmol/L).

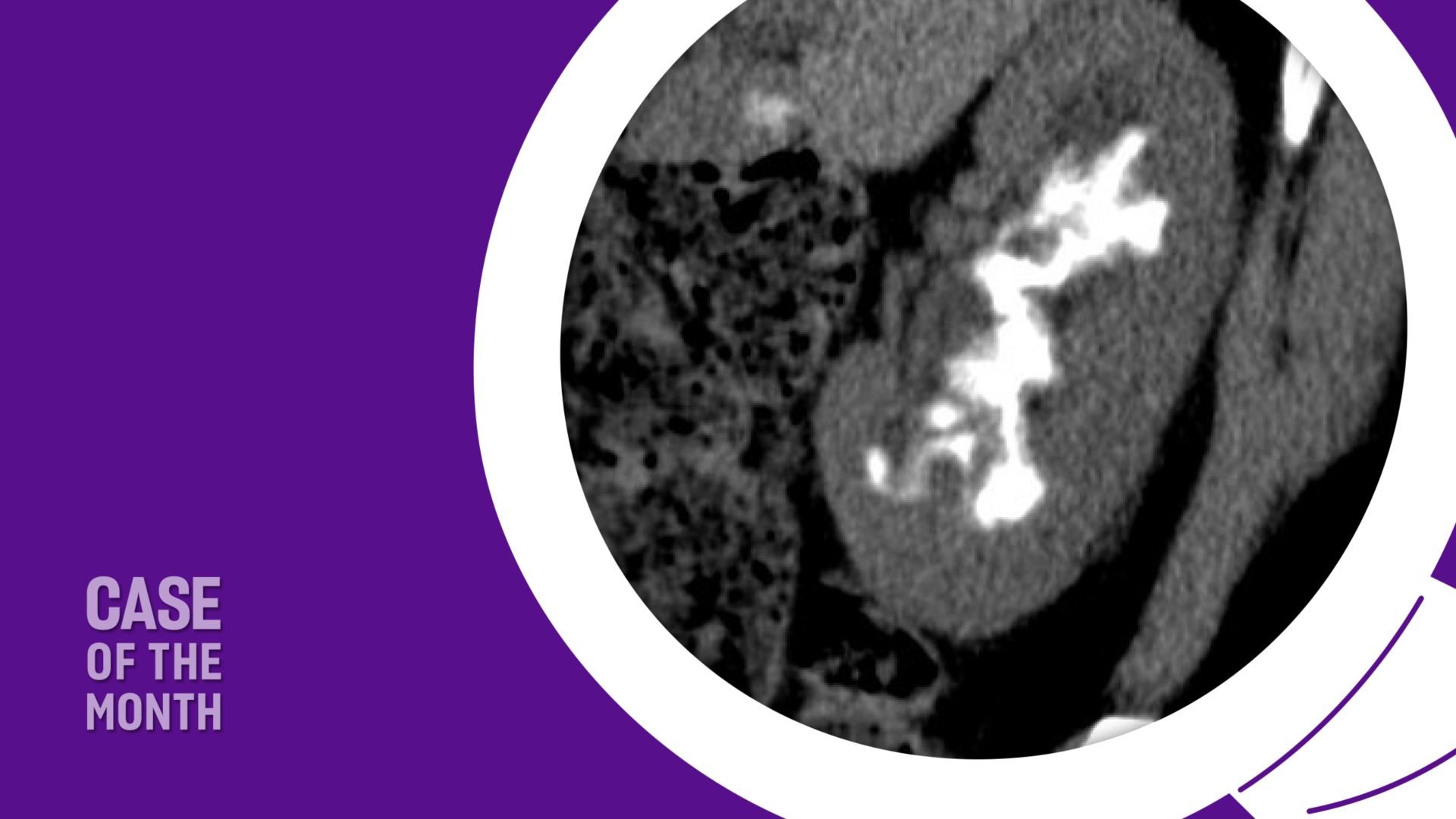

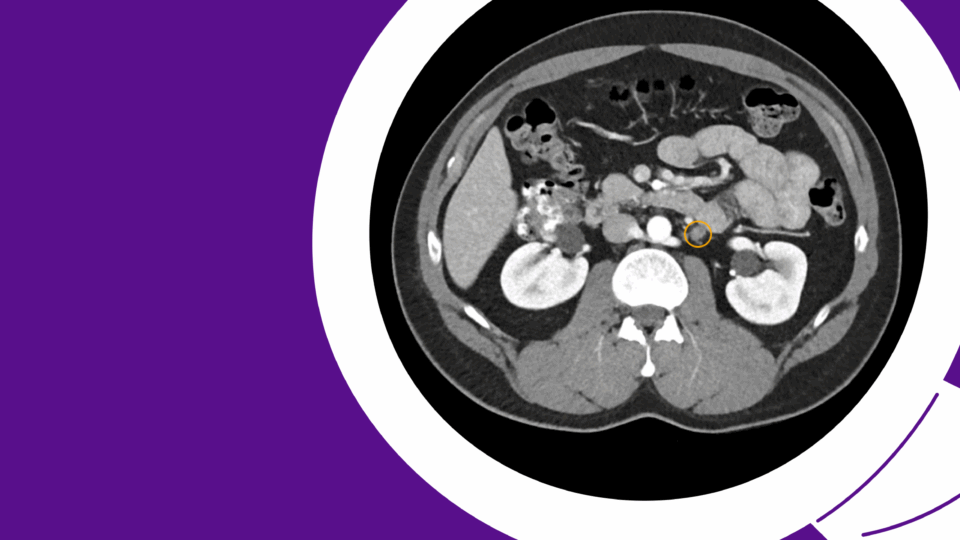

Neither leukocytosis nor hydronephrosis was detected. Subsequent CT imaging demonstrated bilateral non-obstructive EP and calcification of the urothelial mucosa, in addition to encrusted cystitis affecting the posterior bladder wall (Figure 1-3).

Treatment

Upon considering a CU infection and noting the elevated urinary pH of 8, oral linezolid at a dosage of 600 mg twice daily was commenced, and a bladder catheter was inserted. A prolonged urine culture confirmed the presence of >100,000 CFU/mL of CU, which demonstrated sensitivity exclusively to linezolid, vancomycin, and teicoplanin. A right 12F Mono J stent was subsequently placed to facilitate urinary drainage.

After Five Days: After five days of antibiotic therapy, the patient’s renal function showed signs of improvement (creatinine 3.72 mg/dL; 329 μmol/L), though he required one session of hemodialysis. Following the restoration of normal blood pH levels, urinary acidification therapy was initiated. Oral acetohydroxamic acid—a urease inhibitor—was administered and maintained for 30 days (at a dosage of 250 mg/24 hours), in conjunction with oral linezolid.

After Two Weeks: Two weeks into treatment, urine cultures became negative, and urinary pH decreased to 5.5. Throughout the initial phase of acidification, blood pH, and magnesium levels were closely monitored with bi-daily blood tests, producing no reported complications. A right Double-J stent was placed, enabling the patient to be discharged on oral L-methionine (500 mg administered every 12 hours) with a scheduled follow-up.

After Two Months: Two months following the commencement of L-methionine therapy, the initial ultrasound of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder indicated considerable improvement of EP.

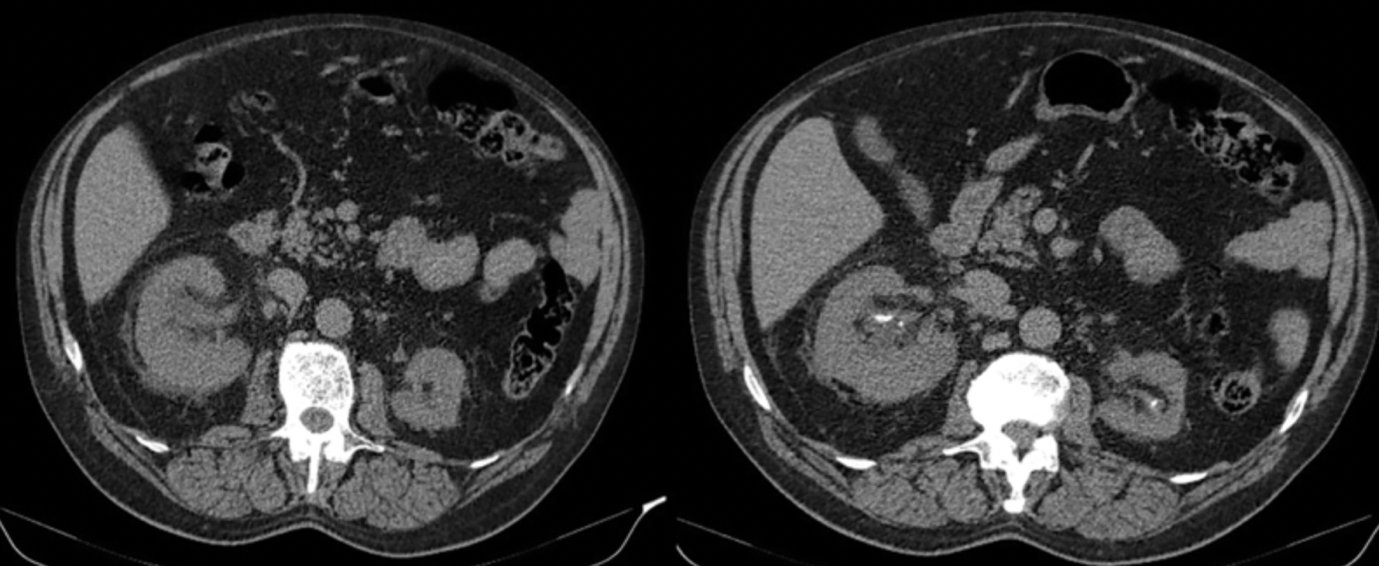

After One Year: In collaboration with the patient and under meticulous monitoring, the oral acidification regimen was sustained for an entire year. Subsequent CT imaging revealed marked resolution of EP (Figure 4). A residual 7-mm calcification was ultimately extracted via right retrograde intrarenal surgery. During this treatment period, creatinine levels remained stable, and urinary pH consistently ranged between 5 and 5.5, with no new indications of CU infection.

Discussion

EP is one of the most challenging diseases to treat in urology due to its frequent misdiagnoses and chronic and refractory nature. The recommended approach is a multimodal treatment combining antibiotics, urinary acidification, urinary diversion, and surgery as a last resort. Specific antibiotic therapies, such as linezolid, teicoplanin, or vancomycin, have been shown to effectively treat the infection within the first week, leading to rapid patient recovery. The additional acidifying treatments aim to reduce calcifications.1

One of the primary challenges is the early diagnosis of calcified urinary tract infections (CU). Suspicion should arise in the presence of sterile pyuria, alkaline urinary pH (usually between 8 and 9), struvite or carbonated apatite crystalluria, encrustation, and calcification of the urothelial mucosa, which can be identified through computed tomography (CT). A prolonged urine culture (over 48 hours) on blood agar in enriched CO2 is also necessary.1,2,3

CU is most commonly sensitive to vancomycin and teicoplanin, which should be used with caution due to the risk of renal failure. Oral linezolid at a dose of 600 mg twice daily has become the treatment of choice due to its oral bioavailability and the fact that it is not nephrotoxic. Additionally, to control encrustations, a urease inhibitor such as acetohydroxamic acid may be beneficial.

Urinary diversion is recommended if obstructive calcifications and stones develop, utilizing nephrostomy tubes or ureteral stents.

After diagnosis, if the patient experiences a high degree of euvolemia or hydronephrosis, placement of a nephrostomy tube or ureteral catheter is advisable for further acidifying instillations and to promote urinary drainage. The off-label use of acidifying solutions, such as Thomas solution, Suby G solution, and DR solution (containing N-acetylcysteine, acetohydroxamic acid, and aztreonam), has been documented, as has the use of non-acidifying irrigations like dimethyl sulfoxide. Although these methods are usually well tolerated, their effectiveness eradicating calcifications can be variable. Instillations should be administered to one kidney at a time, with close monitoring of renal function, acid-base balance, magnesium levels, and potential candiduria.3

Surgery is generally reserved for obstructive uropathy that does not resolve with medical therapy. Ureteroscopy can be performed to treat ureteral calcifications, while percutaneous nephrolithotomy may be indicated for bulky kidney calcifications. In general, endourology is not effective against encrusted urinary tract infections, as encrustations adhere to the mucosa, causing fibrosis and edema, with a tendency to bleed during procedures.

In this case, acetohydroxamic acid was used for one month with no significant changes in renal calcifications. The use of L-methionine at a dose of 500 mg twice daily is commonly recommended as a preventive treatment for infective stones and stent encrustation, and it was effective in reducing EP calcifications.