For the past two decades, public health assessments in the United States have raised concerns over sharply increasing rates of maternal mortality. However, doubts have lingered regarding the accuracy of these estimates, and a study recently published in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology challenges the prevailing estimates, and presents evidence that this is likely a methodological artifact.

According to the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) of the CDC, maternal mortality rates increased by 144 percent between 1999 and 2021, from 9.7 to 23.6 per 100,000 live births. For most of that period, the NVSS/CDC identified maternal mortality by relying on the pregnancy checkbox introduced in 2003 and that now appears on all US death certificates.

“Our findings suggest that the pregnancy checkbox is squarely responsible for a substantial misclassification of deaths.”

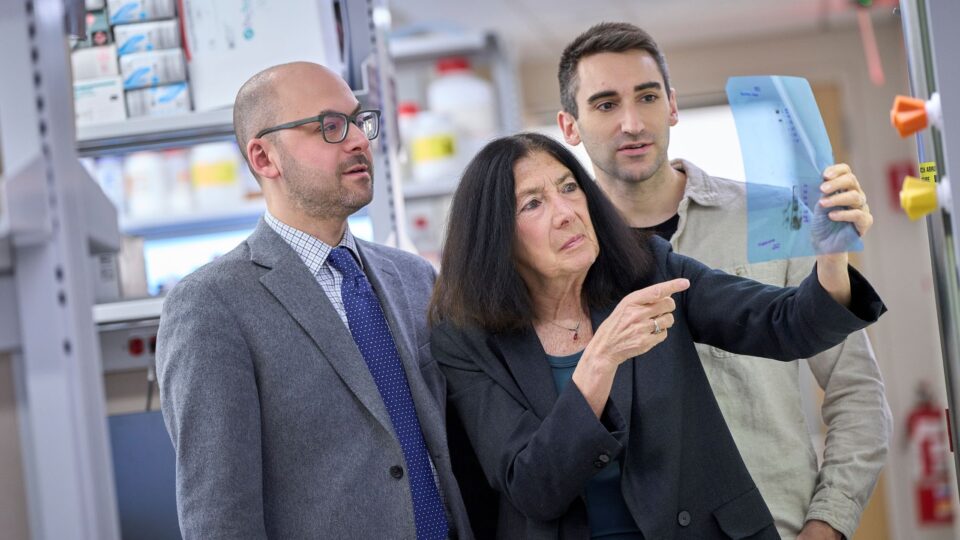

Justin S. Brandt, MD

“What we found was more reassuring,” says Justin S. Brandt, MD, director of the Division of Maternal–Fetal Medicine at NYU Langone Health and a co-author of the study. “Rates of maternal mortality were essentially stable, though we clearly need to do better—especially in addressing the persistent racial and ethnic disparities.”

Pitfalls of the Pregnancy Checkbox

The pregnancy checkbox was designed to correct prior undercounting of maternal deaths, though experts have long recognized that it could drive distortions in the opposite direction.

Reported maternal mortality rates rose sharply in the years after its introduction in 2003, but subsequent studies by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) showed the increase to be an artifact. Errors of ascertainment and misclassification were common. For example, hundreds of women aged ≥70 years were certified as having been pregnant at the time of death or in the year before. These errors led the CDC to stop reporting the official US maternal mortality rates between 2004 and 2017.

In 2018, the NCHS implemented new guidelines restricting use of the checkbox to deaths of pregnant people aged 15 to 44 years. Nonetheless, reported rates continued to soar, nearly doubling between 2018 and 2021.

“My colleagues and I were skeptical of those numbers, in part because they didn’t align with data from the CDC’s pregnancy mortality surveillance system or state-based mortality review committees,” says Dr. Brandt.

Redefining Cause of Death

Suspecting the methodology was unreliable, a multinational research team analyzed the data using a broader approach. Dr. Brandt and colleagues examined a census of all maternal and pregnancy-related deaths from 1999 to 2021. Data were obtained from the NCHS multiple-causes-of-death files which contain information transcribed from death certificates. The files include a single underlying cause of death and up to 20 contributing causes.

The team used two formulations to identify maternal deaths:

- The current NVSS and NCHS methodology, which includes deaths in pregnancy or in the postpartum period, including deaths identified solely because of a positive pregnancy checkbox.

- An alternative, definition-based premise, requiring at least one mention of pregnancy among the immediate, intermediate, or underlying causes of mortality on the death certificate.

The latter formulation was intended to identify only the deaths caused by pregnancy or its management, which epidemiologists refer to as maternal deaths. These are defined as deaths that occur while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes.

The researchers hypothesized that overreliance on the pregnancy checkbox led to the misclassification of many deaths that occurred during or immediately after pregnancy, but that were caused by factors unrelated to pregnancy. While these cases may have been classified on death certificates as maternal deaths, epidemiologists define these as being pregnancy-associated deaths.

“We should work to achieve better ascertainment of maternal deaths and then focus on the areas where there’s real risk.”

Using the alternative, definition-based premise, the researchers recharacterized deaths identified by the NVSS solely because of a positive pregnancy checkbox as pregnancy-associated deaths, not maternal deaths.

A Clearer Picture Emerges

With this definition-based approach, the team found maternal mortality rates to have increased only 2 percent between 1999 and 2021, from 10.2 to 10.4 per 100,000 live births. The drop in maternal mortality rates based on the new formulation brings the US rates well within the range of other high-income countries.

“We saw a decline in direct obstetric deaths, defined as maternal deaths resulting from obstetric complications of the pregnant state, or from treatments related to that state,” says Dr. Brandt. “That makes sense because obstetric care has improved in the last 20 years. We are better capable of managing obstetrical hemorrhage, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, thromboembolism, and other areas.”

On a more granular level, however, the news was less comforting.

Indirect obstetrical deaths—those resulting from previously existing disease or disease that developed during pregnancy and was aggravated by the physiologic effects of pregnancy—rose by 46 percent. Late maternal deaths, from either direct or indirect causes and occurring more than 42 days but less than one year after pregnancy, increased 329 percent. And though maternal mortality rates decreased among pregnant people who were non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic, they remained disproportionately higher for Black people than for other cohorts.

Calling for a Course Correction

“Our findings suggest that the pregnancy checkbox is squarely responsible for a substantial misclassification of deaths, and a consequent overestimation of maternal mortality,” says Dr. Brandt. “We need a course correction, so that we can direct our attention and our efforts more effectively.”

Still, he adds, the study offers no grounds for complacency. “We should work to achieve better ascertainment of maternal deaths and then focus on the areas where there’s real risk. Those disparities in death rates are where we should be channeling more support and funding.”