Artist and endocrinologist Michael B. Natter, MD, is an advocate for the use of sketching to commit to memory details about anatomy, pathophysiology, and more. Inspired to pursue endocrinology due to his own experience with type 1 diabetes, he says his passion for art has served as a learning tool throughout his medical career, and he frequently turns to drawing as a means of communication during patient visits.

Here, Dr. Natter gives his perspective on the role of art in medicine and how mixing the two has made him a better physician.

A Diagnosis and A Discovery

Physician Focus: Can you talk about your personal experience with diabetes? How has it inspired you to pursue a career in medicine, and in endocrinology specifically?

Dr. Natter: Just two weeks after my ninth birthday, I got very sick and no one knew what was going on. I was rushed to the hospital and found to have diabetes; I was in diabetic ketoacidosis.

I was in the ICU for a couple of weeks, and I remember it being incredibly scary. But it also was eye-opening. It sparked my fascination with medicine and with this beautiful symphony that takes place in our bodies that was, in my case, broken.

“Studying for hours on end can be very isolating. I traded my notebooks for sketchbooks and drew everything I could.”

Michael B. Natter, MD

Within endocrinology, I was drawn to the opportunity to form those longitudinal relationships with patients that you see again and again, ultimately pursuing it as my specialty.

Mixing Art and Medicine

Physician Focus: When did you discover your interest in art, and when did you begin to connect it to your interest in medicine?

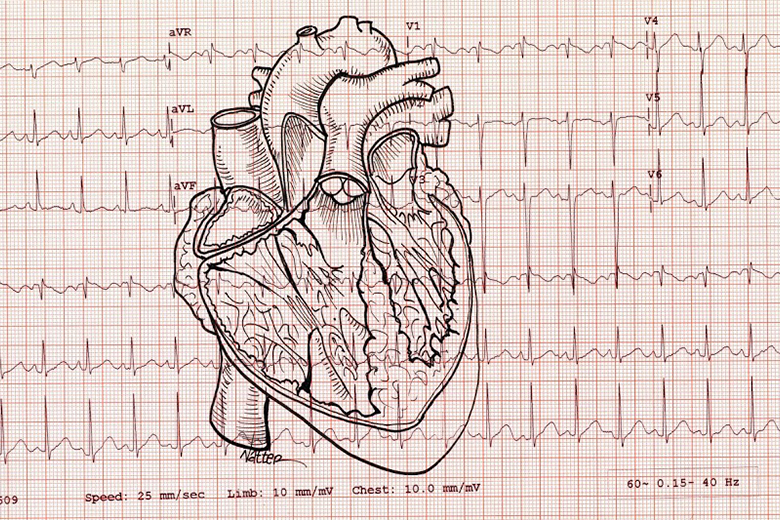

Dr. Natter: I studied fine art as an undergraduate, doing large-scale charcoal drawings, figure drawings, and still lifes. I was always interested in medicine and anatomy, but I didn’t start practicing medical illustrations until I was in my post-bac program.

In those classes, I would draw to learn anatomy, doodling in the margins. Then I would take the test, and all I could remember were my doodles—and it all clicked.

Studying for hours on end can be very isolating. I wanted to do something I enjoyed while studying, so I traded my notebooks for sketchbooks and drew everything I could. To my surprise, I started doing better in my classes.

Sketches, Comics, and More

Physician Focus: You now produce and sell your medical artwork regularly. Is there an overarching focus or theme? What are some of your favorite illustrations?

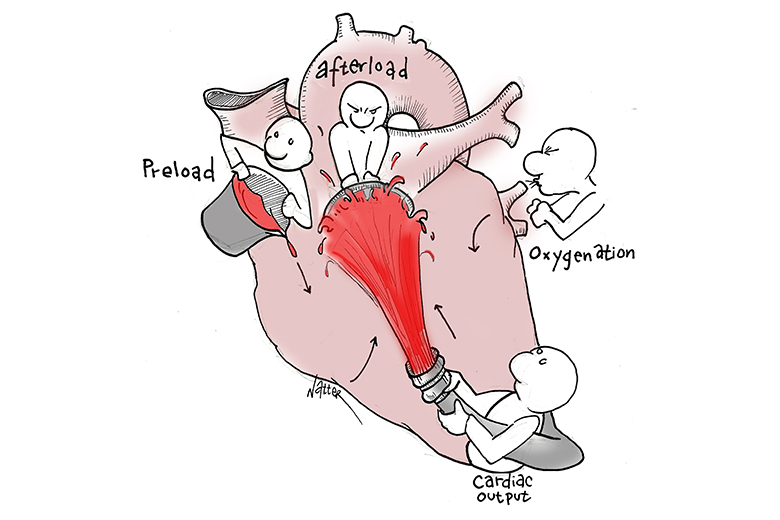

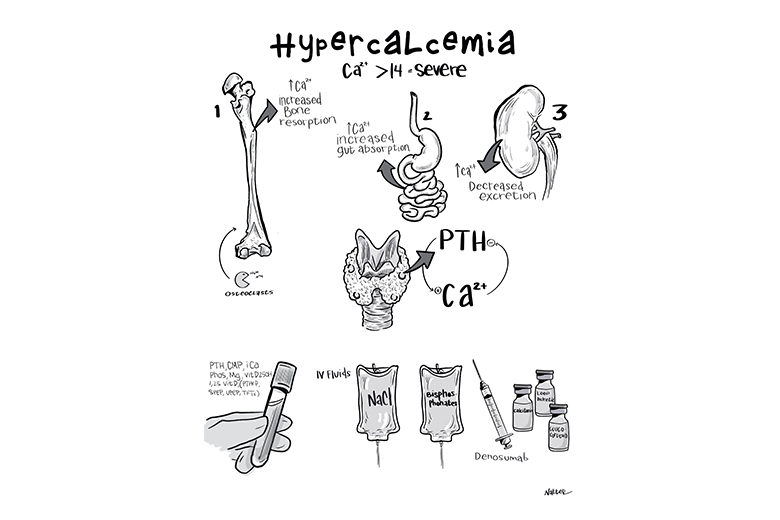

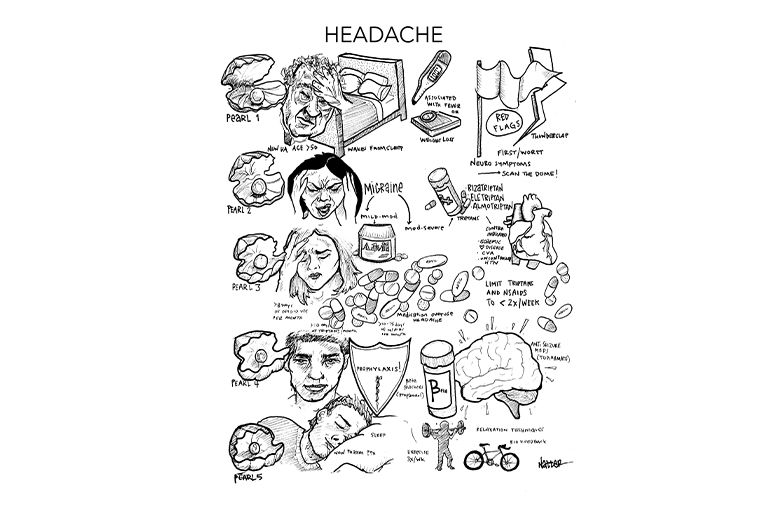

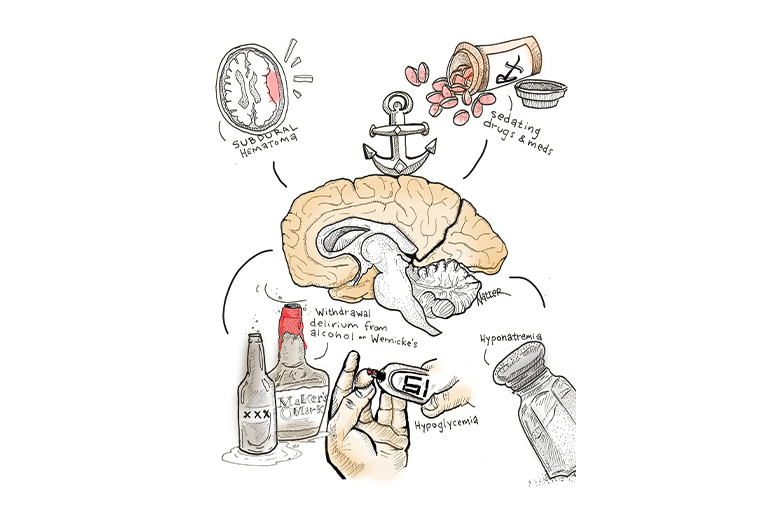

Dr. Natter: My art falls into one of three buckets. The didactic bucket includes the art I created when teaching myself medicine, and the art I now create when teaching medicine to my colleagues, medical students, or patients.

“It’s not the product that’s important, but the process that a provider takes with the patient that’s so powerful.”

There’s the cathartic bucket for graphic novel-type pieces or comics. These are funny or poke fun at some of the insecurities that we experience as we go through medical training. There’s one illustration of what would be me with a Foley catheter and an IV drip of coffee, which pokes fun at the ridiculousness of residency hours.

The third bucket is my fine art that, unfortunately, I’ve done less of since starting medicine because the timing has been tough.

Art as a Process, Not a Product

Physician Focus: How can incorporating art into your medical practice help patients with diabetes, and those with other chronic medical conditions?

Dr. Natter: With chronic illness, especially with conditions like diabetes, you need to have agency and understand the pathophysiology. You need to understand what’s wrong with your pancreas, with your system, with whatever is wrong. For a patient to understand that pathophysiology, a lot of it falls on us as physicians to educate.

The common language is images. You don’t need to speak Spanish to draw a picture.

There’s something magical that happens when I meet a patient for the first time that has diabetes. I always ask them, “Can you tell me what your understanding is of your diabetes?” From there, I’m able to build. Very often, I’m pulling out my sketch pad and drawing for them.

People in the medical world say, “Well, I can’t draw. I’m not an artist.” It’s not the product that’s important, but the process that a provider takes with the patient that’s so powerful. You’re creating rapport, and you’re showing them that you’re taking the time to help them understand—that’s very powerful.

When you are discussing as you’re drawing, I really do think you’re able to get a better understanding from the learner.

More Than Your Title

Physician Focus: How have other physicians responded to your art?

Dr. Natter: I’ve had the opportunity to work with colleagues in dermatology, nephrology, and other fields on medical illustrations for publications. That’s been really fun.

For a lot of adults, there’s this idea of identifying only as one thing. In medicine, I think we become our physician identity, but there’s so much more to us that is valuable, important, and worth celebrating. It’s important that we acknowledge and talk about those aspects of ourselves. Not only because it makes us more human, but also because I believe it makes us better doctors.