As the availability of next-generation sequencing (NGS) becomes increasingly critical to the treatment of gynecologic cancers, persistent underutilization and inequitable access to genetic testing remain significant barriers to care for many patient populations.

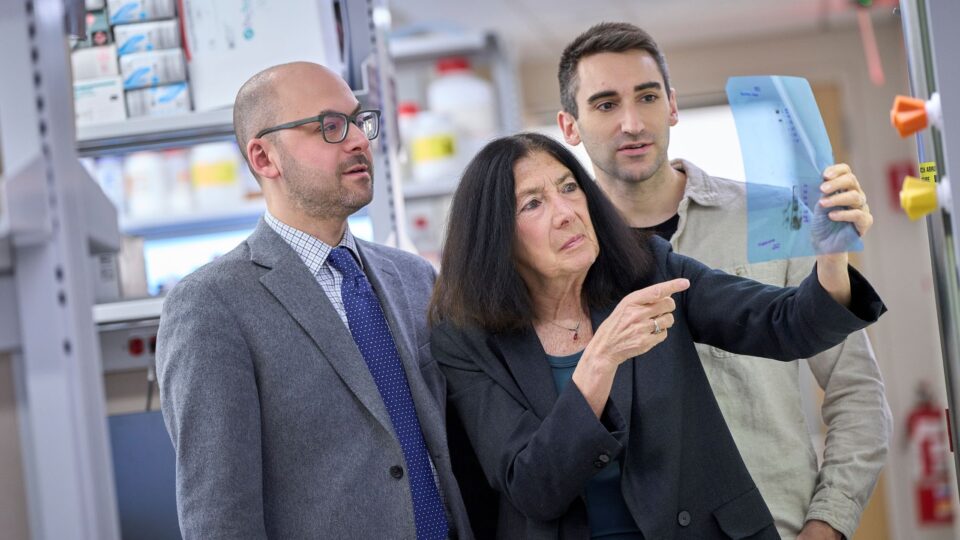

Here, Bhavana Pothuri, MD, director of gynecologic oncology research and medical director of the Clinical Trials Office at NYU Langone Health’s Perlmutter Cancer Center, discusses the specific challenges of universal access to genetic testing and tumor sequencing in these cancers, and how these barriers can be overcome to increase access to the latest clinical trials and treatment options.

Genetic Insights Inform New Guidelines

Physician Focus: Dr. Pothuri, your research focuses on NGS in endometrial cancer. How common is the use of this tool as a standard of care?

Dr. Pothuri: Here at NYU Langone, we now perform NGS on all patients with endometrial cancer right at the time of diagnosis. The entire field is moving in this direction, and we now recognize four distinct molecular subtypes, correlated with prognosis. In fact, the information from NGS has become so important that it will change the staging of some endometrial cancers, and it may also affect treatment. For instance, a stage 1A uterine serous cancer with p53 alteration will be a stage 2 in the soon-to-be adopted Federation in Gynecology and Oncology (FIGO) staging system.

Escalating or De-Escalating Care

Physician Focus: How is NGS helping to inform treatment in endometrial cancer?

Dr. Pothuri: We know from my own research that there is a high rate of pathogenic germline variant detection in those patients who undergo NGS. We have marker-directed immunotherapy options to offer these patients, so undergoing tumor sequencing becomes critical to matching the right patients with appropriate therapies.

“This is a culmination of all of my population health research—we need to do a better job with both preventing and stratifying gynecologic cancers so we can reduce its burden and save lives.”

Bhavana Pothuri, MD

Conversely, under the new staging classification, these insights can actually help us to de-escalate treatment in patients considered low-risk, such as those with POLE-mutated cancers. In Europe, they have already adjusted ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines so that adjuvant treatment is no longer recommended in some patients with stage 1 or 2 cancers that are completely resected.

Disparities Limit Universal Testing

Physician Focus: Despite the recognized benefits of genetic testing, there’s evidence that it’s underutilized. Why?

Dr. Pothuri: It’s true that even before diagnosis, patients at risk for hereditary cancers are not being referred appropriately for genetic testing. We reported a stark example of this, where the vast majority of patients who met National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) criteria for BRCA genetic testing only underwent testing after diagnosis of a BRCA-related cancer. That is a tremendous missed opportunity when we have effective preventive strategies to offer these patients.

As gynecologic oncologists, we see patients once they’re already diagnosed, so education is needed at the primary care, internist, or obstetrician and gynecologist level to flag those patients whose family history meets criteria for genetic testing referral.

“The vast majority of patients who met NCCN criteria for BRCA genetic testing only underwent testing after diagnosis of a BRCA-related cancer. That is a tremendous missed opportunity.”

Notably, we also found that compared to those with private health insurance, publicly insured or uninsured patients were three times more likely to undergo BRCA testing after cancer was already diagnosed. We reported significant racial/ethnic inequity in testing referral in our endometrial cancer study as well.

These findings point to the broad issue of access and implicit bias affecting cancer treatment and participation in clinical trials.

Ensuring Access to the Best Treatments

Physician Focus: What are the repercussions of access inequality when it comes to clinical trials?

Dr. Pothuri: There’s the obvious negative impact on outcomes for patients who could benefit from a trial but aren’t referred. Importantly, we now have evidence that this dynamic is likely also impacting trial results.

For example, we examined data from patients with advanced or recurrent uterine serous carcinomas who received NGS testing and found that Black patients comprised nearly half of this population. Furthermore, 38 percent of Black patients had cancer with CCNE1 amplification, which is associated with poorer outcomes, while no White patients had this alteration.

If a clinical trial of a therapy targeting CCNE1 amplification under-enrolls Black patients, not only will it result in a negative trial, it will miss the opportunity to treat those patients most likely to be affected by the condition—those who experience worse outcomes and need the treatment.

Physician Focus: You also serve as director for diversity and health equity in clinical trials for the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) Foundation. Going forward, what changes can help ensure needed diversity in this space?

Dr. Pothuri: Removing implicit bias from the clinical trial selection process can help diversify enrollment.

In our research, when a pre-screener examined medical charts without seeing patients, we increased enrollment in a trial by threefold in six months; patients enrolled before implementation of pre-screening were all non-Hispanic White, while patients enrolled subsequently were either non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic White. We also need to require mandatory implicit bias, anti-racism, and cultural humility training for all involved in clinical research.

Applying ASCO-ACCC’s Just ASK training will be important, as we know that over two-thirds of patients of diverse populations are willing to go on trials when asked. It’s also critical we address barriers to trial participation, including transportation, loss of wages, and childcare, and ensure protocols are not overly restrictive.

For genetic testing, as the cost comes down, we need universal testing. We are embarking on a study with three Family Health Centers at NYU Langone locations in Brooklyn to offer genetic testing to Hispanic, Afro-Caribbean, and Chinese patients to understand patient uptake and provider feasibility of offering universal testing. We are very excited to activate this study.

This is a culmination of all my population health research—we need to do a better job with both preventing and stratifying gynecologic cancers so we can reduce their burden and save lives.