Urethral diverticula are often asymptomatic and increasingly being discovered incidentally on CT or MRI as cross-sectional imaging has become more widespread. While surgical treatment is considered the gold standard therapy, careful attention to key clinical and surgical considerations is essential for shared decision making with each patient.

In this month’s case report, we present a not-uncommon scenario: an asymptomatic female with an incidental finding of urethral diverticulum who elected surgical excision over watchful waiting.

The case offers an opportunity to highlight not only the rationale for treatment selection and the elements of an uncomplicated surgery, but also potential pitfalls in imaging interpretation, the risk of malignancy with observation, and strategies to optimize post-operative continence outcomes.

Case Highlights:

- The 54-year-old woman was found to have a left-sided urethral diverticulum measuring 2.1 x 1.1 cm with internal debris and mild enhancement, suggesting inflammation.

- Despite no urinary or vaginal symptoms, she elected surgical excision due to potential long-term risks including malignancy.

- She underwent uncomplicated transvaginal diverticulectomy with layered urethral repair, with preserved continence and an uncomplicated postoperative recovery.

- The case highlights the importance of MRI for characterization, counseling on observation risks, and meticulous surgical technique for optimal outcomes.

Patient Case

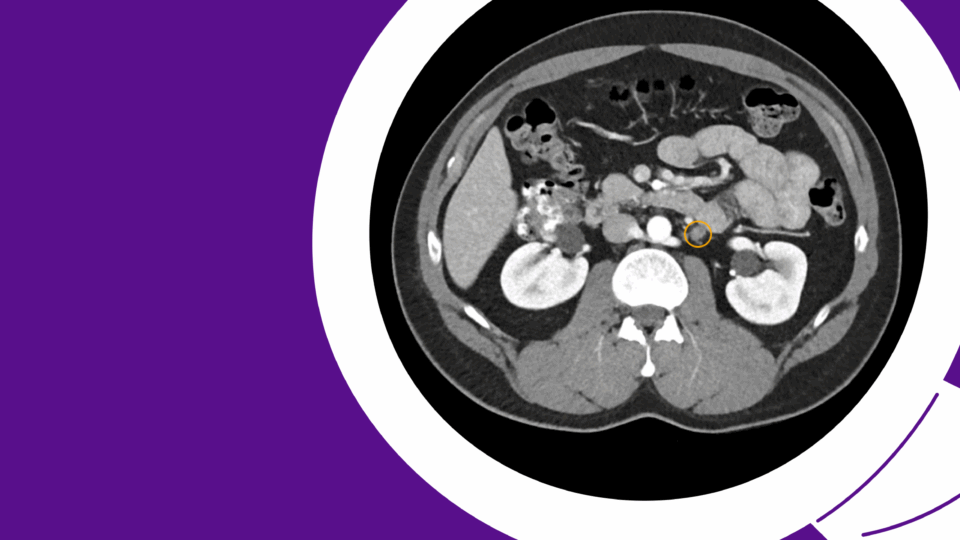

A 54-year-old female was referred for an incidental finding of a urethral diverticulum on CT imaging of the abdomen and pelvis, performed for evaluation of abdominal pain. She denies a history of urinary tract infections, incontinence, or post-void dribbling. She also denies dysuria, vaginal bulge or mass sensation, and dyspareunia. She is gravida 2, para 2, with two spontaneous vaginal deliveries in the remote past. She has been postmenopausal for two years and is not taking hormone therapy. She has no history of pelvic or vaginal surgery.

Her past medical and surgical history is notable only for hypothyroidism and a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Evaluation

Urinalysis and culture: Urine dipstick was positive for moderate leukocytes but otherwise negative. Urine culture was negative. She had a post-void residual of 32 mL.

Pelvic examination: The vaginal mucosa was mildly atrophic. The urethral meatus appeared normal, with no periurethral cystic mass. Mild fullness was noted on palpation of the urethra (left greater than right), with no fluid expressed from the meatus and no tenderness. Moderate urethral hypermobility was present, with a negative cough stress test. No significant prolapse was noted in the anterior, apical, or posterior compartments.

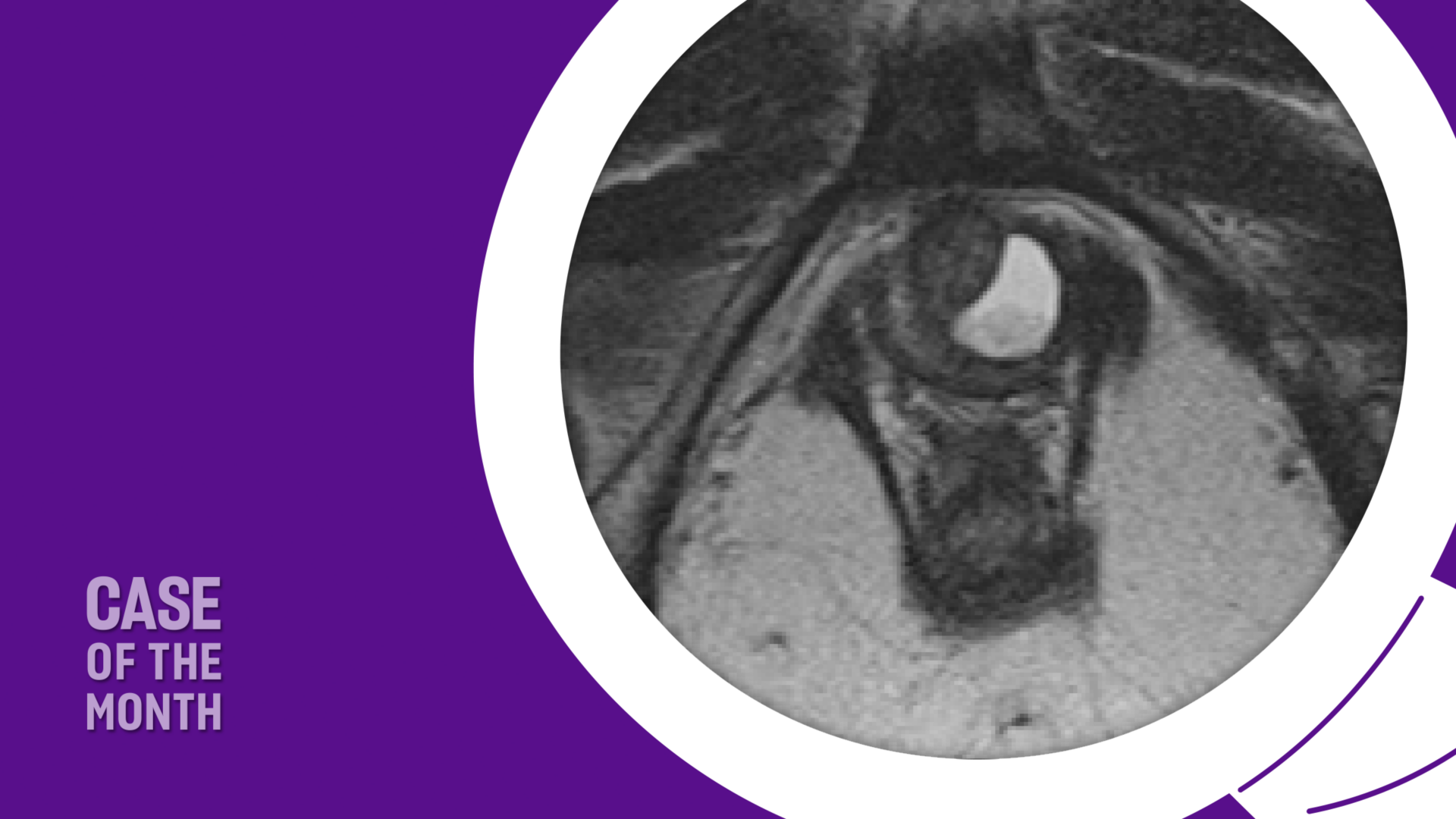

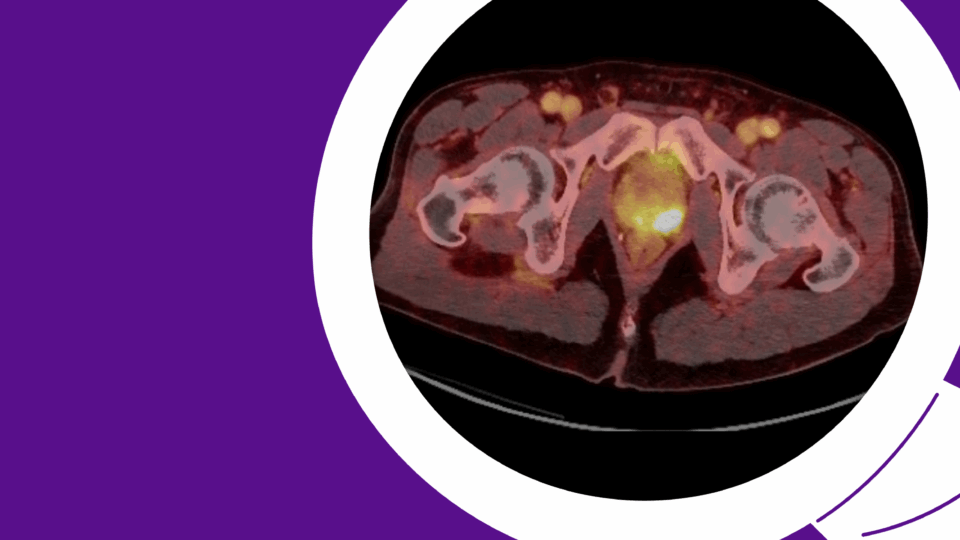

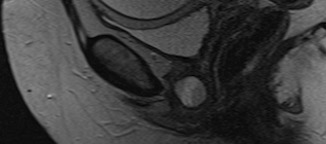

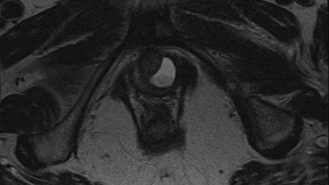

Imaging: Pelvic MRI revealed a left-sided posterior urethral diverticulum with mild enhancement and echogenic debris within the diverticulum (Figures 1 and 2). It measured 2.1 × 1.1 cm and appeared semi-circumferential, with a left-sided communication to the urethra. No stone or mass was identified.

Office Cystoscopy: Cystoscopy was performed using a flexible cystoscope. The urethra was normal in length, caliber, and appearance. A small ostium was identified in the mid-urethra on the left side. The bladder appeared unremarkable.

Management

MRI findings were reviewed with the patient, including the size of the diverticulum, mild enhancement, and the presence of internal debris. Management options were discussed, including watchful waiting, interval MRI imaging, and surgical excision. Although she was asymptomatic, we discussed the long-term risks associated with observation, including potential enlargement of the diverticulum, infection, inflammation, incontinence, stone formation, and the rare risk of malignancy. Given the enhancement and debris, which may indicate inflammation, as well as the potential long-term risk of malignancy if left untreated, the patient elected to proceed with surgical excision.

She underwent uncomplicated surgical excision of the urethral diverticulum with a reconstruction of the urethra in two layers. A 16 French Foley catheter was placed at the beginning of the case, along with a Lone Star vaginal retractor. An inverted U-shaped anterior vaginal wall incision was made overlying the urethra. The periurethral fascia was incised horizontally and carefully dissected off the underlying diverticular sac, with preservation of the periurethral fascial flaps. The diverticulum was sharply dissected circumferentially and transected from the urethra at the ostium, leaving a 3–4 mm opening in the urethral mucosa. The mucosa was closed primarily using 4-0 absorbable suture. The periurethral fascia was minimally trimmed and closed with 3-0 absorbable suture.

The integrity of the two-layered repair was tested by injecting saline through a 16-gauge angiocath alongside the Foley catheter, with no extravasation noted. Finally, the anterior vaginal wall was closed with 2-0 absorbable suture. The Foley catheter was left in place for 7 days and subsequently removed.

The patient’s postoperative course was unremarkable. She reported a good urinary stream with no hesitancy or sensation of incomplete emptying. She denied both stress and urge incontinence and returned to normal sexual activity.

Discussion

Urethral diverticulum is a benign outpouching of the urethra with an epithelial lining and commonly a communication with the urethral lumen. The true prevalence is largely under-estimated as many women are asymptomatic. Age at presentation spans between 20 and 60 years. The diagnosis is most commonly made when a peri-urethral mass is present on vaginal exam and less commonly in the evaluation of urinary incontinence as a presenting symptom. With the increase in cross-sectional imaging, urethral diverticulum can be an incidental finding on routine pelvic imaging such as CT or MRI performed for other reasons.

The classic triad of symptoms historically attributed to urethral diverticulum are dysuria, dyspareunia and post-void dribbling (three D’s). Women can also present with recurrent urinary tract infections (UTI’s), a painless vaginal wall mass and lower urinary tract symptoms such as frequency and urgency. In cases where inflammation or infection have occurred, the communication to the urethra may scar and close and therefore incontinence, dysuria and UTI’s may not be present.

It is important to inquire if a patient has had a urethral bulking injection for incontinence as this mimics urethral diverticulum on cross-sectional imaging and is commonly mistaken by the radiologist as a diverticulum.

Female urethral anatomy is important to understand when evaluating and considering excision for diverticulum. The female urethra is approximately 3 to 4 cm in length. With age and menopause, the urethral length reduces.

The urethra is suspended to the undersurface of the pubic bone by the pubourethral ligaments, which can be stretched or detached by vaginal childbirth. The urethra is comprised of three distinct anatomic layers: 1) the mucosal surface is an epithelial lining of the lumen, 2) there is a spongy submucosa made up of vascular tissue and 3) a distinct layer of periurethral fascia surrounded by longitudinal smooth muscle.

The internal urethral sphincter at the bladder neck is longitudinal smooth muscle innervated by the autonomic sympathetic nervous system via the hypogastric nerve (L1-L4) and is involuntary in terms of control. The external striated urethral sphincter is located in the mid-urethra and is controlled by the somatic nervous system via the pudendal nerve (S2-S4) and is under voluntary control to either contract or relax.

There are prominent peri-urethral glands in the submucosal layer of the distal urethra which drain directly into the urethra. The paraurethral Skene’s glands are located in the vulva on either side of the urethral meatus and lubricate the urethral meatus. Skene’s glands and periurethral glands have been implicated as potentially causative of urethral diverticulum when they become inflamed or infected and then break open into the urethral lumen.1

Greater than 90 percent of ostia are located postero-laterally in the mid to distal urethra. Rarely, urethral diverticula can extend to the dorsal aspect of the urethra in a near circumferential fashion. They can also be multi-loculated.

Evaluation of a urethral diverticulum whether suspected or already identified on imaging includes a thorough history aimed at urinary and vaginal symptoms as well as incontinence, screening urinalysis and urine culture, and a pelvic exam. In women complaining of post-void dribbling, chronic dysuria, and UTI’s, a high index of suspicion should be present in order to diagnose a diverticulum.

The imaging modality of choice is an MRI of the pelvis which has the highest sensitivity of all imaging modalities for urethral pathology. MRI also provides important information necessary for pre-operative planning, including size, location and possible communication with the urethra. In addition, it provides relevant information such as stones within the diverticulum as well as any potential for malignancy. On axial MR imaging the urethra appears “target-like” with three distinct layers of differing intensity.

Ultrasound can also be used to image a diverticulum and can be done via transvaginal, trans-perineal, or trans-labial approach. The diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound is largely dependent on the operator but has advantages of being cost effective without exposure to radiation as well as the ability to image the urethra during Valsalva or movement.

Pathology of urethral diverticula is largely benign (97 percent) and comprised of squamous or columnar epithelial cells. Malignancy is rare but can occur, most commonly as adenocarcinoma, with urothelial and squamous cell carcinoma reported less frequently.1 Malignancy tends to be advanced given the thin layers surrounding the urethra and its close proximity to the vagina, pubic symphysis, and bladder.

Management of urethral diverticulum can be conservative in an asymptomatic female with proper counselling regarding risk of long-term malignancy and interval serial imaging at the judgement of the surgeon. Transvaginal marsupialization has been described as a relatively quick procedure with low recurrence rates. Surgical excision or diverticulectomy involves excision of the entire diverticular sac and a watertight, multi-layered closure of the urethra.

In women with pre-operative complaints of stress incontinence, a concomitant anti-incontinence procedure can be offered or can be staged. Mesh slings are contra-indicated at the time of diverticulectomy because of the high risk of mesh erosion into the urethra. Autologous fascial pubovaginal sling can be done simultaneously and can also offer an extra layer of interposed tissue to lessen the risk of post-operative urethrovaginal fistula. Pre-operative assessment of incontinence with video-urodynamic evaluation can help to differentiate incontinence from the diverticulum versus incontinence from the bladder with stress maneuvers on fluoroscopic imaging. In continent patients, post-operative de novo stress incontinence can occur in 33 percent of patients.2

Surgical excision of urethral diverticula is always accomplished via a transvaginal route. An anterior vaginal wall flap in an inverted U-shaped fashion provides wide exposure of the entire urethral length. If the diverticulum extends on to the dorsal aspect of the urethra, dissection and mobilization of the urethra can be accomplished circumferentially through an anterior vaginal wall incision and vein retractors are very helpful in providing traction on and protecting the integrity of the urethra during this dissection. Rarely a supra-meatal incision can be made if the majority of the diverticulum is located dorsally, or others have described a complete urethral transection to enable excision of the dorsal aspect with re-anastomosis of the urethra.3 Use of a vasoconstrictive injectable agent is very beneficial in reducing periurethral and vaginal bleeding, particularly in young pre-menopausal women.

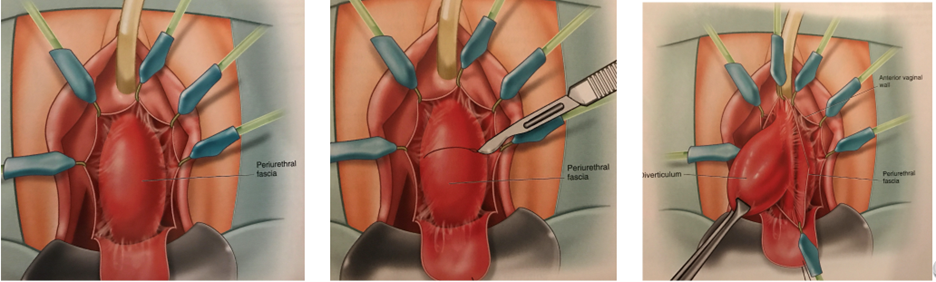

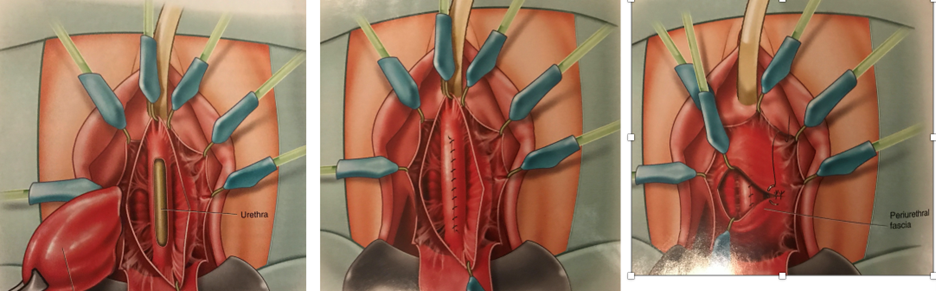

It is important to pay particular attention to creation of peri-urethral fascial flaps before excising the diverticular sac to allow for a two-layered urethral repair. In addition, the ostium should be excised with care to preserve as much urethral mucosa as possible to enable a tension-free closure of the urethral mucosa (Figure 3).4 Rarely, if the remaining urethral mucosa is limited and attenuated, a buccal mucosal flap or local vaginal wall flap can be integrated into the urethral mucosal closure.

A concurrent autologous fascial pubovaginal sling can be placed either for pre-operative stress incontinence or for additional tissue interposition in cases where the local tissues have been damaged by infection, inflammation, or radiation.

A urethral catheter is left in place post-operatively to allow complete urethral healing and the duration of catheterization is at the discretion of the surgeon but generally varies between 7 to 14 days.

a. Inverted-U incision of anterior vaginal wall

b. Transverse incision of peri-urethral fascia

c. Dissection of urethral diverticulum

d. Excision of diverticulum with urethral mucosal defect seen

e. Closure of urethral mucosal defect with running absorbable suture

f. Closure of peri-urethral fascia in transverse manner

Figure 3. Steps for surgical excision of urethral diverticulum. Reprinted with permission from Vaginal Surgery for the Urologist, Nitti VW, Rosenblum N and Brucker BM, Chapter 10 Urethral diverticulectomy, pages 118-123, Copyright Elsevier, 2012.4

Outcomes regarding incontinence following urethral diverticulectomy are reported as 5 to 23 percent de novo stress incontinence. In those who underwent concomitant pubovaginal sling, 83 to 90 percent reported resolution of pre-operative stress incontinence. Stress incontinence persisted post-operatively in 38 to 72 percent in those with pre-operative stress incontinence and no pubovaginal sling.5,6

Success rates of urethral diverticulectomy range between 84 to 98 percent. Re-operation rates for persistence or recurrence of diverticulum range between 2 to 13 percent, with follow-up ranging between 12 to 50 months. Risk factors for recurrence include multiple diverticula at presentation, proximal location, and prior surgery or pelvic radiation. In addition, recurrence can occur with new Skene’s gland infection, trauma such as vaginal birth, and incomplete resection of initial diverticulum.7

Conclusions

Female urethral diverticula can be a cause of urinary incontinence and lower urinary tract symptoms in a small subset of women and are most commonly diagnosed today as an incidental finding on cross sectional pelvic imaging. The finding of an anterior vaginal wall mass in the sub-urethral location should raise an index of suspicion for urethral diverticulum. MRI is the imaging modality of choice with a high sensitivity in detecting peri-urethral pathology.

Management of diverticula should be a collaborative decision between the patient and the surgeon, with the understanding that long-term watchful waiting carries with it a small risk of malignancy. Assessment of pre-operative stress urinary incontinence is important to improve post-operative continence outcomes and a concomitant pubovaginal sling can be offered in this setting with high success rates. The keys to surgical success are complete surgical excision with identification of the ostium and a multi-layered urethral repair to avoid the risk of urethrovaginal fistula.

References

- Serrell EC, et al. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2021;48(3):599-616. DOI.

- Lee UJ, et al. Urology. 2008;71(5):849-853. DOI.

- Rovner ES and Wein AJ. J Urol. 2003;170(1):82-86. DOI.

- Nitti VW. Urethral diverticulectomy. In: Nitti VW, Rosenblum N and Brucker BM, eds. Vaginal surgery for the urologist. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2012: 118-123.

- Enemchukwu E, et al. Urology. 2015;85(6):1300-1303. DOI.

- Barratt R, et al. Neurourol Urodyn. 2019;38(7):1889-1900. DOI.

- Greiman AK, et al. Arab J Urol. 2019;17(1):49-57. DOI.