Research led by specialists at NYU Langone Health’s Comprehensive Epilepsy Center is helping to pinpoint biomarkers—and untangle potential root causes—of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP), a rare but well-recognized cause of death in people with uncontrolled seizures.

Each year, SUDEP is estimated to occur in 1 out of every 1,000 people with epilepsy. It affects all age groups and until recently little was understood about how the condition of patients with epilepsy or the characteristics of seizures might lead to death.

“It wasn’t enough to tell patients and families that it was uncommon—we wanted to uncover what could be done to prevent it.”

Orrin Devinsky, MD

“There was a recognition by physicians and the patient community that we needed to better understand why some patients can have a single tonic–clonic seizure and die from it,” says Orrin Devinsky, MD, chief of the NYU Langone Epilepsy Service. “It wasn’t enough to tell patients and families that it was uncommon—we wanted to uncover what could be done to prevent it.”

Uncovering a Mechanism

Dr. Devinsky was a principal investigator involved in the Center Without Walls—a scientific collaborative funded by the National Institutes of Health and launched in 2014 to enhance the understanding of SUDEP. The virtual center yielded several research initiatives characterizing the biomarkers and neuropathology involved in SUDEP.

Separately, Dr. Devinsky and his team created the North American SUDEP Registry—the most comprehensive SUDEP registry to date—which has gathered and centralized information on the epidemiology of SUDEP in more than 400 patients. The foundational studies powered by both the collaborative and the registry have led investigators to understand a likely mechanism involved in SUDEP: central respiratory arrest and cardiac arrhythmia following tonic–clonic seizures.

“These studies have emphasized that SUDEP is not a phenomenon limited to patients with severe seizures. SUDEP happens to patients with milder disease as well.”

Orrin Devinsky, MD

“Importantly, these studies have emphasized that SUDEP is not a phenomenon limited to patients with severe seizures,” notes Dr. Devinsky. “We are beginning to build an understanding of all the factors that contribute to a given patient’s risk—but SUDEP happens to patients with milder disease as well.”

Specific SUDEP Biomarkers

In a third research initiative, Dr. Devinsky is collaborating with Daniel Friedman, MD, associate chief of the NYU Langone Epilepsy Service, to further investigate the clinical, genetic, and physiological mechanisms of SUDEP by combining biospecimens and lifestyle information from patients living with epilepsy—as well as those who have died from SUDEP and their family members. For example, the researchers are analyzing how measures such as heart rate variability may associate with SUDEP, pinpointing new biomarkers, including reduced short-term low-frequency power.

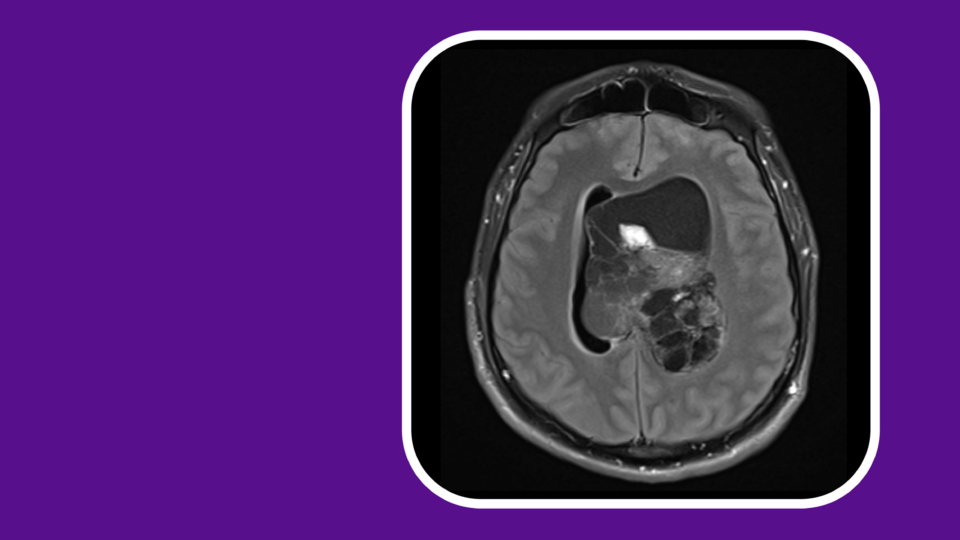

Along with MRI analyses of structural changes in the brain and electroencephalograph (EEG) data identifying the duration of typical postseizure changes in brain activity, these data can be used by physicians and researchers to stratify patient risk of SUDEP and point to potential areas for intervention.

“We want to understand which patients are at highest risk so we can target counseling and find mechanistic pathways for preventive treatment.”

Daniel Friedman, MD

“We want to understand which patients are at highest risk so we can target patient counseling, identify surrogate end points for interventional studies, and find mechanistic pathways for preventive treatment,” says Dr. Friedman.

Stratifying Risk, Targeting Intervention

With the help of artificial intelligence (AI), the researchers are also using biomarker data from the studies to build a machine learning tool that predicts the individual risk of SUDEP, with the goal of assisting clinicians in identifying high-risk patients. “The idea is that you could input a patient’s symptoms, medical history, and other information, and learn that their risk per year is, say, 1 in 2,800. If they are consistent with their medication routine, their risk might decline to 1 in 5,100 per year, for example,” says Dr. Devinsky.

For now, preventive strategies for SUDEP are in the form of lifestyle modifications and wearable technologies. Alcohol overuse, obesity, missed medications, and sleeping alone are known risk factors that could potentially be modified through patient education.

Technologies such as wearable watches with seizure-related alerts have been developed specifically to lower SUDEP risk.

“The majority of SUDEP cases occur when the patient is alone,” adds Dr. Friedman. “If a higher-risk patient lives alone, a neighbor or friend could get alerts in the event of a seizure and know to check on the patient—potentially saving their life.”