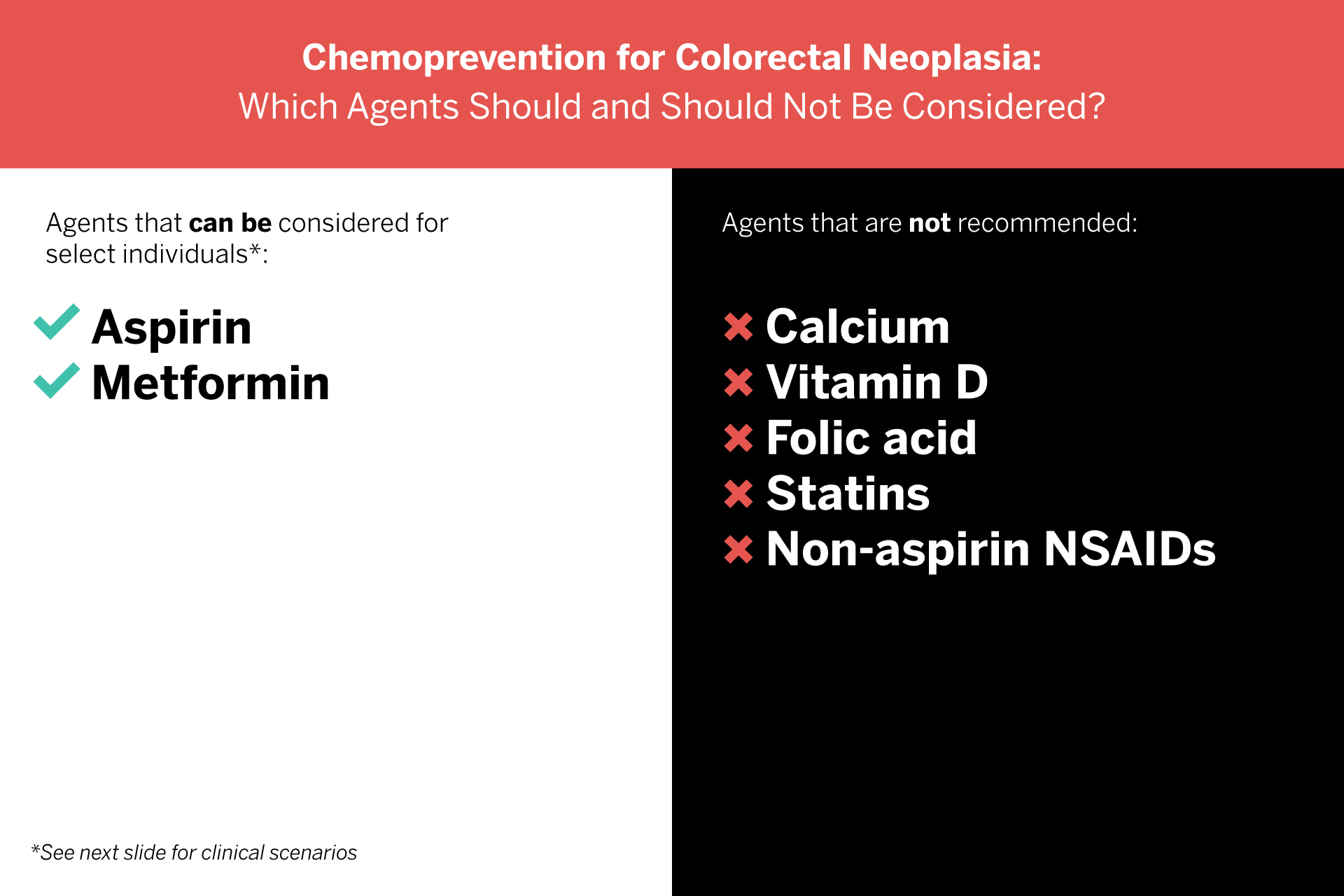

While there is growing interest among both patients and clinicians in chemoprevention for colorectal neoplasia, currently only aspirin or metformin should be considered, according to expert recommendations commissioned by the American Gastroenterological Association.

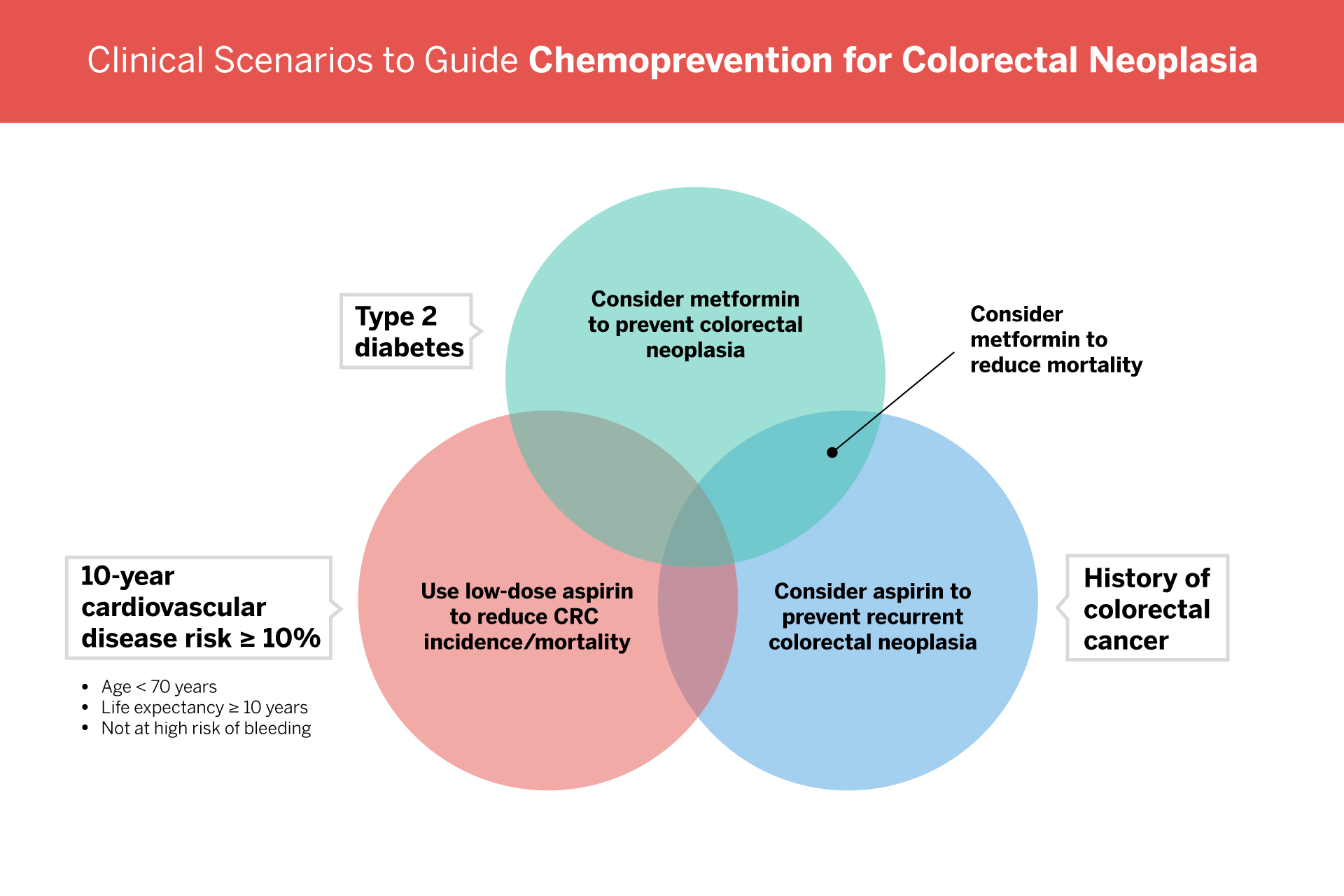

“Aspirin has the best evidence for colorectal neoplasia, but it’s not for everyone,” says gastroenterologist Peter S. Liang, MD, MPH, first author on the article. “There is less evidence for metformin than for aspirin. But for people with type 2 diabetes, metformin should be considered.”

Best Practice Advice

With a slew of chemoprevention agents under various stages of investigation, Dr. Liang and colleagues, including Aasma Shaukat, MD, MPH, the Robert M. and Mary H. Glickman Professor of Medicine and Gastroenterology, sought to provide an updated review of well-studied medications that have been evaluated in clinical trials.

“These represent some of the most updated and practical recommendations on chemoprevention for colorectal cancer,” Dr. Shaukat says.

“These represent some of the most updated and practical recommendations on chemoprevention for colorectal cancer.”

Aasma Shaukat, MD, MPH

While they report strong evidence for the use of low-dose aspirin to reduce colorectal cancer incidence and mortality, it should only be considered for patients younger than 70 who are at risk of cardiovascular disease, and its benefit must be weighed against the risk of bleeding.

“If someone shouldn’t be taking aspirin for heart disease prevention, it isn’t recommended that they take it for colorectal neoplasia prevention,” says Dr. Liang.

In contrast, no clear chemopreventive benefit can be found for calcium, vitamin D, folic acid, or statins. Non-aspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are not recommended due to the high risk of adverse events.

Navigating Patient Conversations

Medications that lower cancer risk have great appeal from a patient perspective, Dr. Liang explains. But in some cases, patients may take medications for chemoprevention that have not been prescribed. As the new recommendations point out, this may be more harmful than helpful.

“When physicians talk to their patients, it’s useful to ask if they are taking anything on their own,” says Dr. Liang. “We hope this can serve as a resource as they navigate those conversations.”