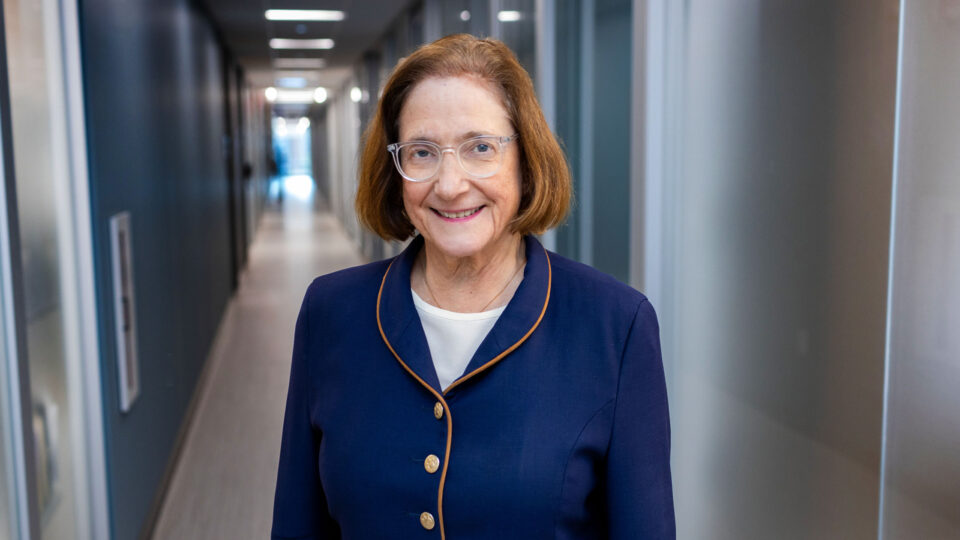

Kathryn Colby, MD, PhD, the Elisabeth J. Cohen, MD, Professor and chair in the Department of Ophthalmology, describes an “a-ha” moment that led her to consider removal of Descemet membrane without donor tissue transplant as a possible treatment for Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD). It was 2013, and new research was emerging on the pathophysiology of FECD, as well as anecdotal case reports of corneal clearance in FECD without insertion of donor corneal tissues.

Dr. Colby heard a colleague present at EuCornea on a small series of cases involving deliberate descemetorhexis. Convinced that this strategy should work in FECD, she decided to try it.

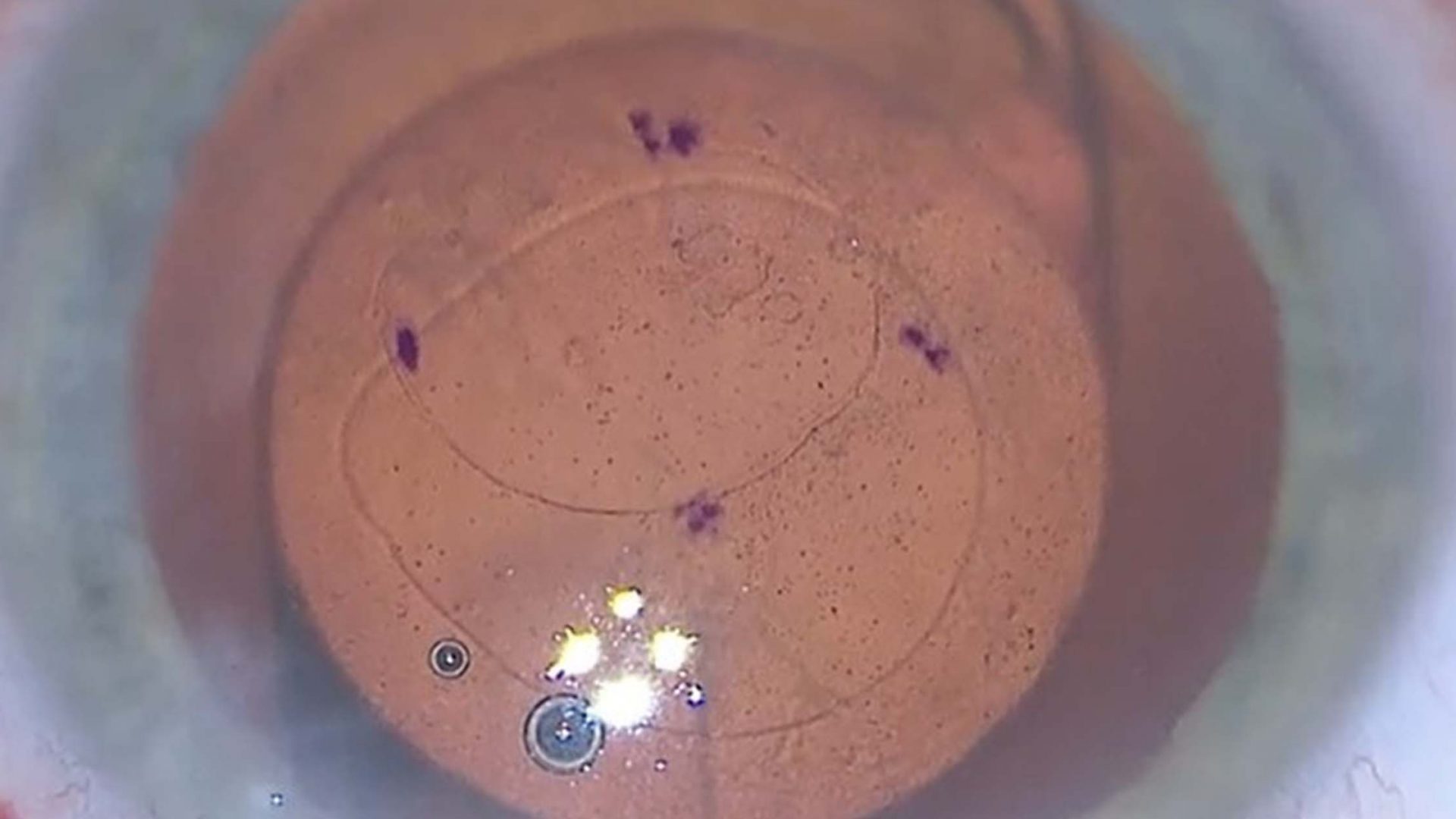

In a report in Cornea, Dr. Colby describes how these observations led to the development of her Descemet stripping only (DSO) procedure, its current status, and what successful DSO tells us about the pathophysiology of FECD.

“The corneal world was skeptical when we began discussing our results in 2016,” she says, “but this is a revolution in the surgical treatment of Fuchs disease. It’s been a phenomenal arc from discovery to practice.”

The Role of ROCK Inhibitors

FECD accounts for more than a third of the corneal transplants performed in the United States. For many years, the only transplantation option consisted of penetrating keratoplasty, which carries risk of tissue rejection and blindness. In 2012, endothelial keratoplasty became the most commonly performed keratoplasty procedure, and selective keratoplasty became the primary surgical treatment for FECD.

As clinical evidence mounted for minimally invasive descemetorhexis without keraplasty, the next major advance was a report that a Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor—ripasudil, approved in Japan as glaucoma therapy—rescued two patients with slow-to-clear FECD.

“We know that the endothelial cells don’t divide after birth, but this showed that they retain some replicative capability,” Dr. Colby explains.

A Promising Case Series

The DSO procedure pioneered by Dr. Colby combines removing the center part of the cornea’s endothelial layer with the novel application of a ROCK inhibitor to trigger cell migration and regeneration.

“Equipping the body with its own means to heal is always preferable to foreign transplant, and we now understand that endothelial cells do in fact have that capability once damaged cells are removed,” she says.