Mood disorders often coexist with disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBI), and both lack fully effective therapies. While selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are first-line treatments, they can cause anxiety and gastrointestinal issues—and, in children exposed in utero, increased risk of DGBIs and cognitive and mood disorders. Yet the processes that mediate the therapeutic and adverse effects of SSRIs are unknown.

Two multi-institutional studies co-led by pediatric gastroenterologist Kara G. Margolis, MD, the head of research for the Pediatric Neurogastroenterology and Motility Disorders Program at Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone, shed light on these questions—and point toward novel treatment pathways that could mitigate both the gestational and postnatal risks of SSRIs.

“We’ve found persuasive preclinical and epidemiological evidence that the effects of SSRIs are mediated by the gut-brain axis,” Dr. Margolis explains. “And in an animal model, we show conceptually that targeting SSRIs to the gut epithelium may preserve their benefits for pregnant mothers while protecting both fetuses and mothers from negative impacts.”

Here, we overview the approach and main findings from the two studies and share what’s next for the research.

How are SSRIs linked to DGBIs?

For over a decade, Dr. Margolis has been a pioneer in investigating the effects of serotonin and SSRIs on the gut, where 95 percent of the body’s serotonin is located.

Studying mouse models, she and her colleagues revealed multiple serotonin-mediated trajectories of gut and brain development, suggesting a common etiology for conditions that affect both, such as autism spectrum disorder. They also hypothesized that disruptions in gut-brain serotonin signaling might engender the adverse gestational effects of SSRIs, and that preventing such disruptions might eliminate those effects.

What were the team’s population-based findings?

In a retrospective cohort study, published in Nature Molecular Psychiatry, the team investigated associations between gestational SSRI exposure and offspring DGBI in over 52,000 children. The largest population-based study of such links to date, it is also the first to control for maternal depression, as well as to rely on clinician diagnoses rather than parental self-reports, and to follow up beyond early childhood.

The team analyzed Danish registry data on children born from 1997 to 2015, comparing those whose mothers continued SSRIs during pregnancy with those whose mothers discontinued SSRIs before pregnancy. The main outcomes were first diagnosis of a childhood DGBI (including functional disorders involving nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain disorders, diarrhea, and/or constipation), or physician-prescribed laxative. Members of each cohort were tracked for up to 15 years.

Key findings:

- SSRI-exposed children had a 15.9 percent estimated incidence of any DGBI, versus 14.7 percent for the unexposed cohort.

- That heightened risk was driven principally by functional constipation.

- The results are consistent with preclinical studies by Dr. Margolis’s group linking gestational serotonergic manipulations to changes in gastrointestinal motility.

A prospective birth cohort study, published in Gastroenterology, showed an even more pronounced link. The study classified 408 mother–child dyads into three groups: maternal depression and SSRI/serotonin-norepinephrine uptake inhibitor (SNRI)-exposed; maternal depression without SSRI/SNRI exposure; and healthy controls. The team found that children in the SSRI/SSNI-exposed group had a threefold risk for functional constipation across the first year of life.

“Serotonin is critical for how fast or slow the gut moves, and to the development of neuronal subsets expressing that neurotransmitter in both the gut and the brain,” Dr. Margolis observes. “It’s not surprising that the most common GI symptom associated with prenatal SSRI exposure would be constipation mediated by dysfunctional gut-brain signaling.”

Can targeting SSRIs to the gut prevent adverse effects?

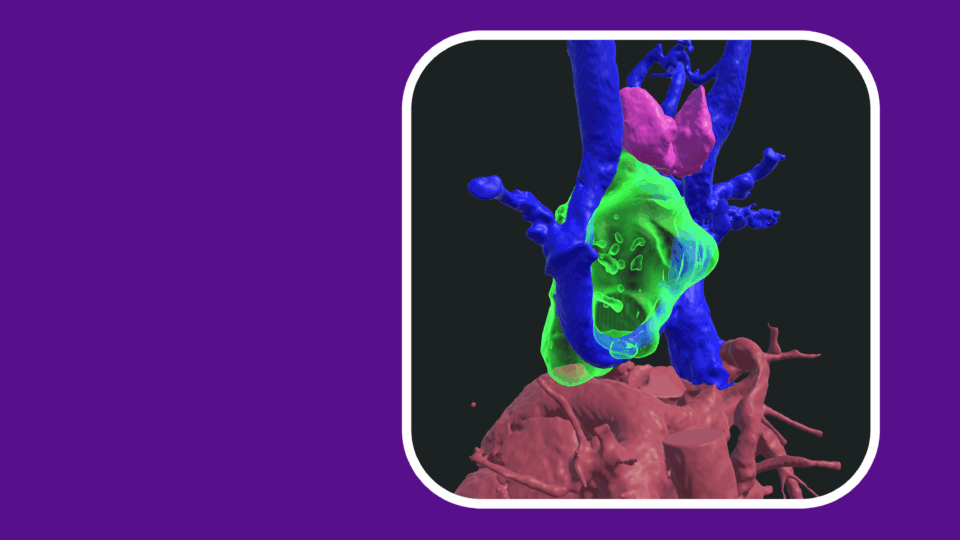

The Gastroenterology publication also reported on a novel targeting strategy for SSRIs: inhibiting the serotonin reuptake transporter (SERT) only in the intestinal epithelium, rather than systemically. This approach, they posited, could deliver the drugs’ beneficial effects via the patient’s gut-brain axis without affecting fetal development. It might also lessen the adverse effects experienced by many SSRI users, such as abdominal pain and anxiety.

Key findings:

- In mice, blocking SERT only in the gut epithelium produced antidepressive- and anxiolytic-like phenotypes without the common adverse effects of systemic SSRIs.

- Unlike total SERT ablation, this approach did not adversely affect enteric nervous system development or intestinal motility from gestation through adulthood.

- Ablating afferent projections of vagal sensory neurons reversed the positive effects of epithelial SERT ablation, suggesting that gut to brain communication, via vagal signaling, mediates those effects.

“Our results suggest that SSRIs don’t need to target the brain directly, at least in mice,” says Dr. Margolis.

Does this mean antidepressants should not be used during pregnancy?

No, this does not mean SSRI use is always inappropriate for pregnant women since depression can also have negative effects on the fetus. But it does highlight the importance of developing antidepressants that do not cross the placental barrier—perhaps through the mechanisms explored in the group’s animal research.

“These two studies are the first to show that developmental SSRI exposure leads to a potentially increased risk of developing a disorder of gut-brain interaction, as opposed to the gut or brain alone,” says Dr. Margolis.

What’s next for this research?

Dr. Margolis and her colleagues are now investigating drug delivery systems that could selectively block SERT in the intestinal epithelium. They are also identifying biomarkers in the intestinal microbiome of mothers and infants that could portend which children will go on to develop gut-brain dysfunction. “If we can find a way to translate these findings into therapies,” she says, “it could be paradigm-shifting.”

Disclosures

Dr. Margolis has patents related to the drug delivery systems discussed in this article.