For anyone who missed the 2024 AACR Annual Meeting, director of the Perlmutter Cancer Center at NYU Langone Health Alec Kimmelman, MD, PhD, discussed some of the most interesting and important topics during a recent interview with Marc K. Siegel, MD, at Doctor Radio on Sirius XM. Subscribers can hear the full discussion here, the interview extract below has been edited for length and clarity.

Dr. Siegel: One of the things that the American Association for Cancer Research focused on is this idea that younger people are getting cancer, and maybe it has something to do with biological aging. Why is this happening? Is it processed foods? Is it alcohol? What’s causing the increase that we’re finding in cancer rates in younger people?

Dr. Kimmelman: It’s multifactorial, and I don’t think we really, truly have a handle on it. Each cancer is probably going to be a bit different. I mean, exposures are certainly something that is in play here. The food we eat, the microbiome, all of them are in play here. And you’re right, cellular aging is an emerging field that may explain some of this. But I don’t think we have the answer yet in a way that could be useful, to help us at this point.

Dr. Siegel: What about personalized medicine? Is everybody going to have a different treatment for their cancer?

Dr. Kimmelman: Absolutely. The goal is to be able to take a patient’s tumor—and this is something that we’re building here, and offer a lot of already—and analyze it comprehensively, assessing the genetic makeup and histological makeup. We aim to understand the unique nature of each patient’s tumor. What do we know about it? How do we expect it will behave? What drugs will this respond to? And you have to do that both accurately, but also relatively quickly, because you can’t wait months to start cancer therapy on patients.

“The ultimate goal will be to take a patient’s tumor, make a diagnosis, and have them leave the same day with a personalized cocktail of chemotherapeutics—hopefully oral drugs.”

Alec Kimmelman, MD, PhD

The ultimate goal will be to take a patient’s tumor, make a diagnosis, and have them leave the same day with a personalized cocktail of chemotherapeutics—hopefully oral drugs that target specific mutations in their tumor—so their particular tumor receives the optimal therapy. All of this has to be paired together. It’s what we’re doing now, and it’s only going to become more prevalent.

Dr. Siegel: You’re working with CRISPR genetic alterations. We’re going into almost a science-fiction world where we’re altering genetics as well as proteomics to create treatments, right?

Dr. Kimmelman: You’re right, we have tools now that we’ve never had before. We can do gene editing, which is what CRISPR is. And we can actually change individual nucleotides or base pairs in a tumor. So, you can imagine scenarios where you can correct defects. What we’re going to try and do, and we have been doing, is to make the tumors more immunogenic.

The mRNA vaccine technology is also very powerful. It allows a very rapid way to personalize vaccines. At AACR, longer-term results of an mRNA vaccine for pancreatic cancer were announced. That team showed that there are sustained immune responses out to a couple of years. So, I think it’s an exciting time. And going back to your point about translational research, this is the ultimate example, where you can make a personalized vaccine for a patient in a fairly quick amount of time. We have to do better, but it’s just amazing how fast that can go.

Dr. Siegel: How does all of this extend to healthcare disparities? Because one of the things we didn’t mention yet is cost, and cost is enormous when you have new treatments, especially if it’s genetic editing. How are we going to make sure everybody gets access to this?

Dr. Kimmelman: One of the main focuses of a cancer center is to study the disparities that occur in our catchment area. So, we spend a lot of time first understanding what the disparities are in incidence. We have robust epidemiological programs to understand what are the disparities for cancer in our own area, which can also apply more broadly. There are whole community outreach and engagement programs that we have here to make sure that patients understand what therapies are available to them and what the important preventative measures are, like vaccines for HPV. We want to make sure that they have access to all of the latest and greatest therapies.

“We also have programs here to ensure that everyone gets access to clinical trials, regardless of their socioeconomic status. That’s very important to us.”

So, we spend a lot of time making sure that patients are aware and have access to quality care. We also have programs here to ensure that everyone gets access to clinical trials, regardless of their socioeconomic status. That’s very important to us. Ultimately, as a healthcare system, the country is going to have to figure [this] out, and there’s going to be an issue in terms of the cost of healthcare. But I can say here we make sure that all of our latest clinical trials and latest developments are available to everybody.

Dr. Siegel: One final question about AACR, which is liquid biopsy, diagnosing things from blood tests. Where are we heading in the future?

Dr. Kimmelman: There’s a ton on this now, and I think people have probably heard about this in multiple different contexts.

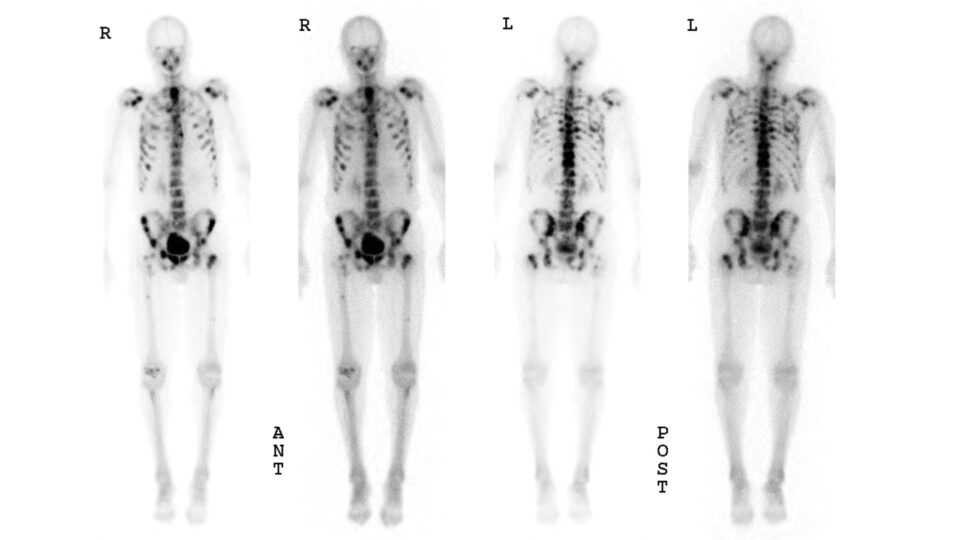

One is in the context of early detection. I think the trials are still ongoing in terms of the utility of it in that space. The other area is using it to follow patients with cancer. And this is where we’re very involved, because I think this is really the future of oncology, which is we’re going to need to follow patients with imaging to see when their tumors come back. But that takes hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of cells to see anything on MRI or a PET scan. But by taking a simple peripheral blood draw, we can sequence that blood and look for mutations from tumors, and then detect the cancer before we even see it on any sort of imaging.

So, there’s an early detection for following therapy, and this allows us to change our therapies more quickly. But we can also follow what the next best therapy is because we could see that the cancer developed a resistance mutation, and that this drug will be more effective than the drug that you’re on, and we can make those changes early. And then [there’s] deescalating therapy. If a patient just had surgery and the circulating tumor DNA goes away, that patient might be someone who we can deescalate therapy in because we don’t see circulating tumor DNA.

These are things that we use consistently here, and make sure that all patients have access to, but it really is the future.