Prostatic abscesses are uncommon but potentially serious infections, more frequently seen in older men with chronic comorbidities. While many providers may rely primarily on antibiotics alone for the treatment of small- to medium-size abscesses, combining antibiotic therapy with transperineal drainage may accelerate patient recovery and lead to better outcomes.

Not all urology residents are skilled and confident in performing transperineal drainage. Ensuring that all such residents have the opportunity to master this technique during their training is a key step in enhancing the care and quality of life for patients with these painful complications.

To highlight the benefit of having proficiency in transperineal drainage, this Case of the Month describes its use to successfully manage a prostatic abscess in a 78-year-old male. Draining the abscess permitted a quick correction of the patient’s fever and rising white blood cell (WBC) count.

Case Highlights:

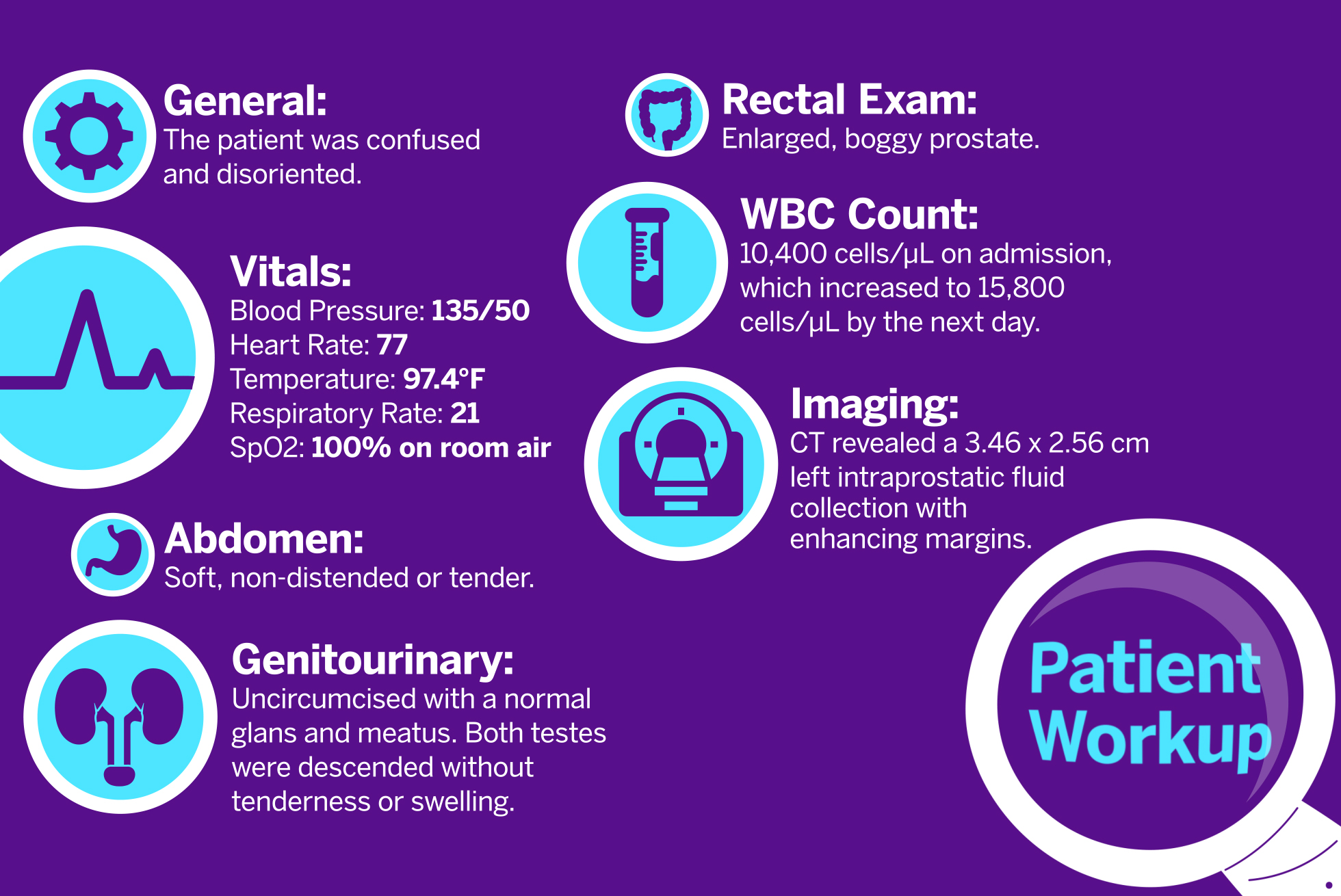

- The patient presented with a > 3 cm abscess, fever, confusion, and a rising WBC count reaching >15,000 cells/μL (microliter).

- Interventional radiology could not perform a transgluteal drainage due to the small size of the abscess and recommended intravenous antibiotics.

- With concern for the patient’s rising WBC count, urology performed a transperineal drainage.

- Two days after the procedure, the patient’s WBC count dropped below 10,000 cells/μL and his fever resolved.

Case Presentation

The patient presented to the emergency department following multiple episodes of falling. He had a medical history of type 2 diabetes, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis, hypertension, and a left below-the-knee amputation secondary to gangrene. The patient had been lethargic for five days, with markedly reduced oral intake. His family found him on the floor at home, prompting his presentation.

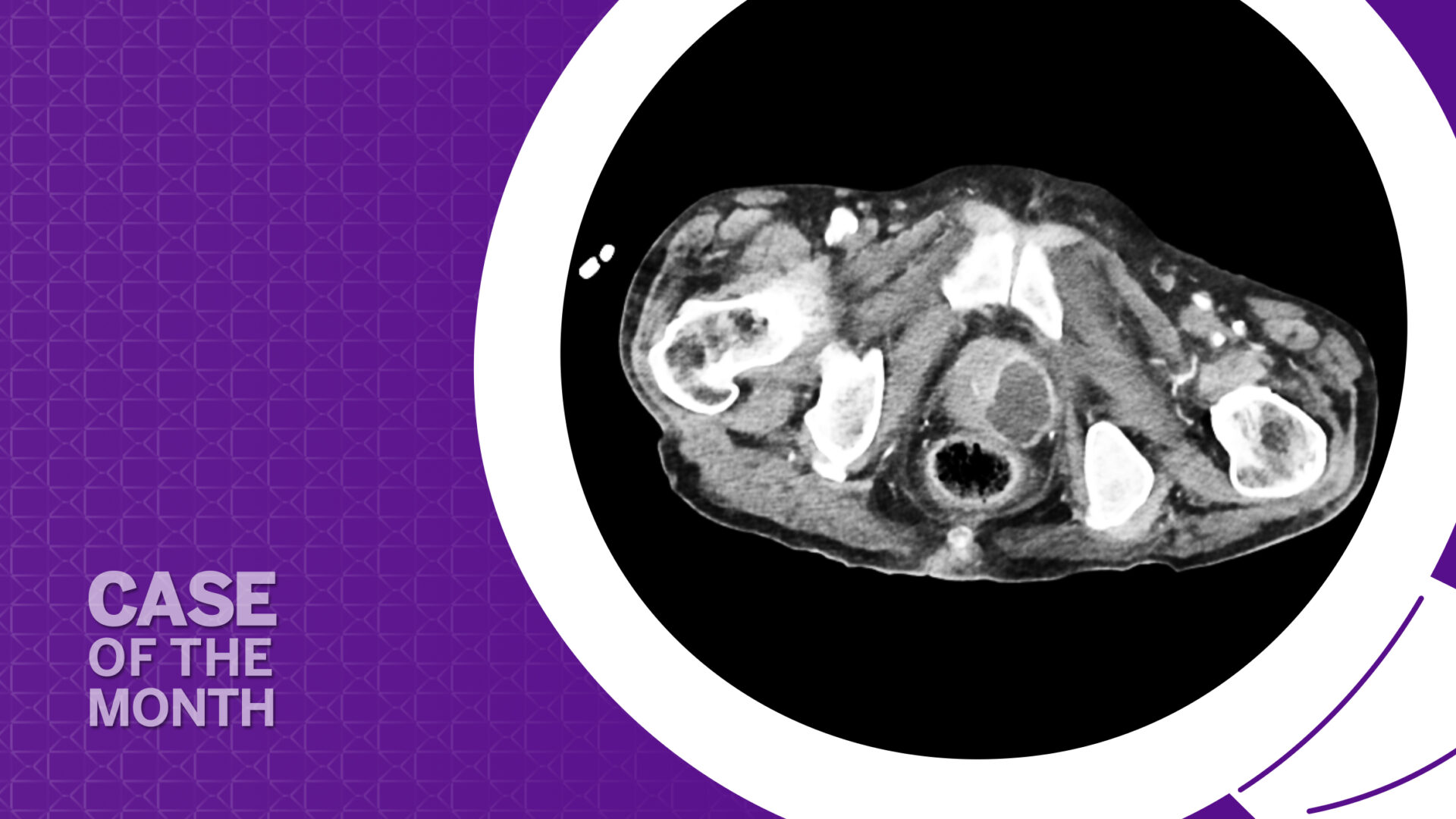

On admission, the patient was febrile, with a temperature of 101.3 degrees F. He was cleared by trauma surgery after CT imaging, but an incidental finding on the CT scan prompted a urology consult: a “left intraprostatic fluid collection most compatible with abscess.” The patient was subsequently admitted for management of a prostatic abscess, failure to thrive, and recurrent falls.

Physical examination of the patient was notable for an enlarged, boggy prostate, while blood work revealed a rising WBC count (Figure 1).

Management

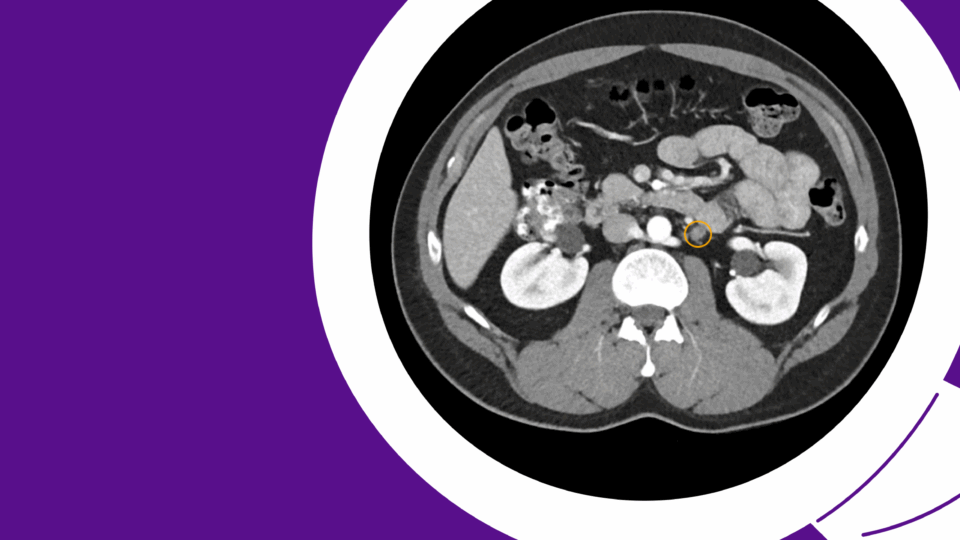

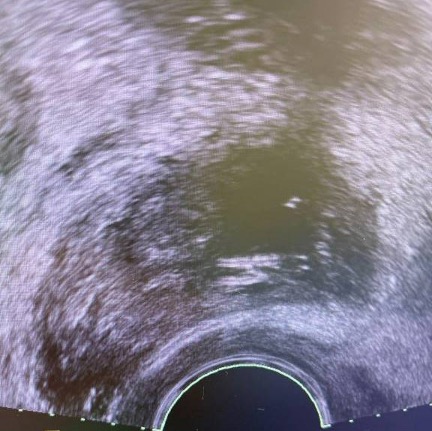

The patient was initiated on intravenous Zosyn and intravenous fluids. Interventional radiology (IR) was consulted for potential abscess drainage. However, IR did not drain the collection, as it was too small to target with a pigtail catheter placed by a transgluteal approach. Instead, IR recommended continued intravenous antibiotics with reimaging for resolution of the collection. Since the patient’s WBC count continued to rise, the urology service decided to perform a transperineal drainage of the prostatic abscess under transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) guidance (Figure 2).

A total of 13 ml of purulent fluid was drained from the abscess. Cultures grew Klebsiella pneumoniae, which was sensitive to ceftazidime. The infectious disease team recommended a regimen of 2 grams of ceftazidime administered during hemodialysis. Blood cultures subsequently confirmed K. pneumoniae.

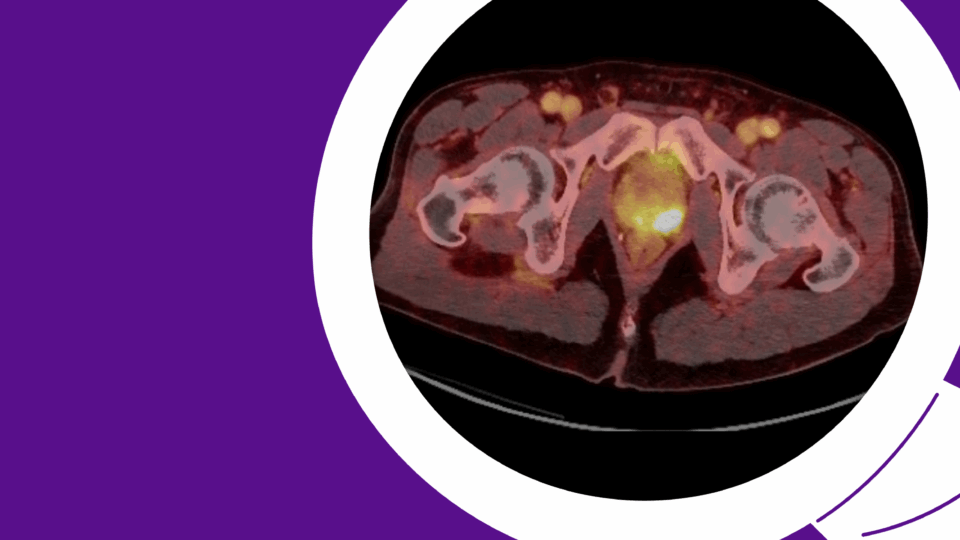

Follow-up CT imaging two days after placement of the catheter confirmed the appropriate position of the catheter and a decrease in the abscess size. The patient’s WBC count decreased to 9,500/μL, and he became afebrile. After five days, the drainage from the pigtail catheter ceased, and a subsequent CT scan demonstrated resolution of the abscess cavity, allowing for catheter removal (Figure 3). The patient completed a four-week course of intravenous antibiotics, as per infectious disease recommendations.

Discussion

This case spotlights the advantage of having transperineal drainage in the armamentarium of the urologist. Instead of waiting weeks for intravenous antibiotics to treat the infection, our urology service’s use of transperineal drainage allowed the fever to break and WBC to decrease within just two days.

However, many urology residents are increasingly lacking experience and ease with the technique, even though they do develop expertise in transperineal biopsy. Integrating training in transperineal drainage would therefore be straightforward and beneficial.

This case also offers an overview of the challenges and considerations in managing prostatic abscesses.

Prostatic abscesses are most frequently observed in men aged 50 to 60, but they occur in all age groups.1 In younger patients, the presence of a prostatic abscess warrants investigation for underlying comorbidities.1 Historically, prostatic abscesses were associated with chronic bacterial prostatitis, voiding dysfunction, and neurogenic voiding dysfunction. However, chronic medical conditions are now recognized as significant risk factors. These include diabetes mellitus, renal failure, liver cirrhosis, and immunocompromised states such as rheumatologic conditions.1 Genitourinary instrumentation is also a leading cause of prostatic abscess formation. According to one report, a history of an indwelling urethral catheter, recent urethral instrumentation, and recent prostate biopsy were present in 29, 17 and 8 percent of prostatic abscess cases, respectively.2

Diagnosis is primarily confirmed through imaging modalities such as CT, MRI, or TRUS of the prostate. Management depends on the abscess size and patient symptoms.

For abscesses smaller than 2 cm with multiple loculations, as well as small abscesses associated with leukocytosis and minimal symptoms, antibiotic therapy based on urine or blood culture sensitivity or both can be initiated for two to three weeks, at which point the patient should be reevaluated. If the abscess persists, TRUS-guided needle aspiration and/or perineal drainage with a pigtail catheter, or transurethral resection/unroofing of the abscess cavity should be performed.3

If the abscess is larger than 2 cm and associated with severe lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), urinary retention, sepsis, or leukocytosis, then TRUS-guided transperineal abscess drainage with a pigtail catheter and urinary diversion with a suprapubic catheter may be considered. Another alternative may be to engage IR to perform a transgluteal drainage. If there is persistence of the abscess despite drainage, transurethral unroofing of the large abscess should be considered.3 The advantage of transperineal or transgluteal drainage over unroofing is the preservation of antegrade ejaculation. For all large abscesses, prolonged antibiotic therapy for four to six weeks is required.

The successful outcome of this case underscores the importance of careful monitoring and a tailored multidisciplinary treatment approach.

References

1. Ackerman AL et al. (2018). Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients with Prostatic Abscess in the Post-Antibiotic Era. Int J Urol; 25(2):103–110. DOI.

2. Elshal AM et al. (2014). Prostatic Abscess: Objective Assessment of the Treatment Approach in the Absence of Guidelines. Arab J. Urol.; 12:262–268. DOI.

3. Vyas JB et al. (2013). Transrectal Ultrasound-Guided Aspiration in the Management of Prostatic Abscess: A Single-Center Experience. Indian J. Radiol. Imaging; 23:253–257. DOI.