Can trauma be inherited? Research says yes—but until now, less was understood about the mechanism of intergenerational trauma and its impact on specific neuropsychiatric outcomes. New and ongoing studies led by NYU Langone Health neuroscientist Moriah E. Thomason, PhD, are untangling how various biological and environmental factors characterize typical and atypical neurodevelopmental trajectories in children.

“We know that trauma can be transmitted intergenerationally. The question is, does this happen even before birth?”

Moriah E. Thomason, PhD

“We know that trauma can be transmitted intergenerationally, from parents who experienced maltreatment in childhood to their own children,” explains Dr. Thomason. “The question is, does this happen biologically, even before birth, and if so, what does that actually look like in the brain’s circuitry?”

Mapping Trauma’s Roots, Before Birth

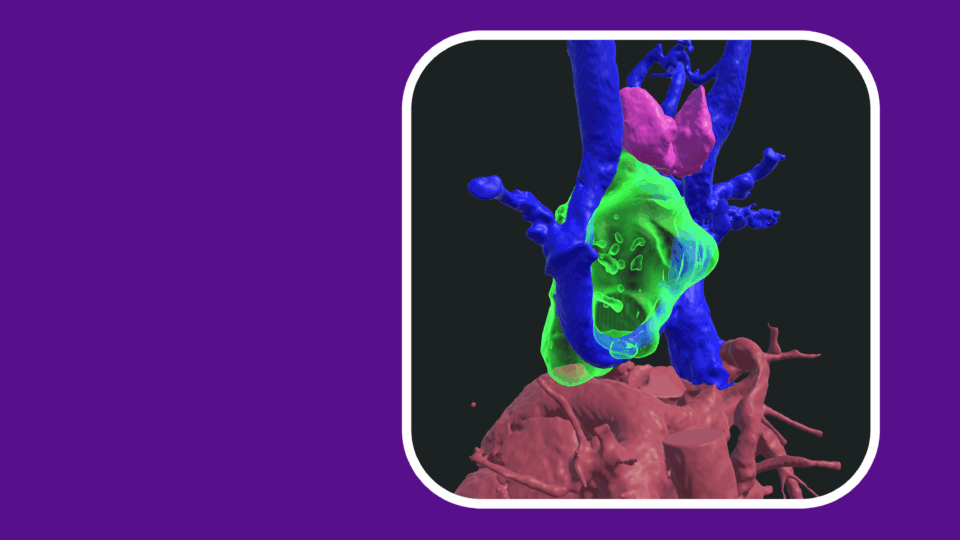

Building on earlier research using resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) to create a blueprint of fetal brain connectivity, Dr. Thomason studied the fetal amygdala–cortical function—critical to the regulation of emotion and fear—in scans of 89 healthy pregnant women between the late second trimester and birth. The women were primarily from households with low resources and socioeconomic status, who themselves had relatively high childhood maltreatment as measured by the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire.

“Earlier studies have found an association between mothers who reported emotional neglect during childhood and infants with stronger connectivity between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex,” Dr. Thomason explains. “We sought to eliminate the potential influences of the postnatal environment by examining these brain regions before birth, when biological influences contribute maximally to our measures.”

A positive coupling was found between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex and premotor areas of the developing brains scanned in utero, confirming an association between the mothers’ experiences of childhood maltreatment and the circuitry of their babies’ brains before birth. Further, higher amygdala connectivity between the amygdala and the left prefrontal cortex was observed in fetuses of mothers who experienced greater childhood trauma.

Brain Differences: Biological Adaptation?

It is well understood that positive amygdala–prefrontal cortex connectivity is associated with higher threat sensitivity and anxiety disorders in children and adults; in this pattern, healthy response regulation is interrupted by irregularities in the limbic circuitry. Through longitudinal studies, Dr. Thomason and her team will probe whether sensitization of that circuitry beginning in utero leads to lasting developmental and neuropsychological differences.

“We can’t assume this change in the pattern of association between these brain regions is necessarily a disadvantage.”

“Biology is evolutionarily intelligent,” she explains. “It may be that we are born with brains adapted and optimized for the environment we grow into. We can’t assume this change in the pattern of association between these brain regions is necessarily a disadvantage.”

With increased understanding of the role of both genetics and environment on inherited trauma–associated outcomes, researchers hope to pinpoint the interrelationship between those developmental inputs and specific neuropsychiatric outcomes—and target early interventions accordingly.

Pooling Data to Mitigate Generational Trauma

NYU Langone is one of 25 sites involved in the HEALthy Brain and Child Development Study, a national consortium following pregnant women and children from birth through early childhood, to observe the impact of various biological and environmental exposures on behavior and development.

With a five-year grant from the NIH, Dr. Thomason and colleagues from the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry will contribute to the most comprehensive dataset to date on early development based on biospecimens, brain imaging, patient-reported history, and other inputs. Data collected will enable researchers to analyze the factors that contribute to children’s brain development, and identify exposures to trauma, substance use, and other environmental influences that may either increase their risk of problems or increase their capacity for resilience.

“We are only just beginning to understand the breadth of neurodevelopmental consequences stemming from trauma in all its forms,” says Dr. Thomason. “From micronutrients in developing teeth to toxins in urine, we are uncovering biological clues to lead us toward interventions that can help mitigate the negative effects of intergenerational trauma.”