Management of stage IIA/B seminoma has traditionally relied on chemotherapy or radiation, treatments that achieve excellent cure rates but expose young patients to substantial long-term morbidity. As survivorship has become a central consideration in testicular cancer care, clinicians are increasingly challenged to balance oncologic efficacy with preservation of long-term health and quality of life.

Advances in surgical technique, nerve-sparing approaches, and perioperative care have renewed interest in primary retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) as a viable option for carefully selected patients with limited-volume metastatic seminoma.

This case highlights the use of primary RPLND in a patient with stage IIA seminoma. It demonstrates how a modern, nerve-sparing approach can achieve disease control while preserving function and avoiding systemic therapy, with ctDNA incorporated to support postoperative surveillance.

Case Highlights:

- AUA guidelines now list primary RPLND as an option for select patients with stage II seminoma.

- Careful patient selection is critical, particularly in patients with limited-volume retroperitoneal disease, normal tumor markers, and a longer time from orchiectomy to recurrence.

- In the case, the patient underwent nerve-sparing RPLND with an ERAS protocol, was discharged on POD 2, and remained disease-free at one year with normal ejaculatory function.

- Follow-up includes tumor-informed ctDNA for early detection of microscopic disease, in conjunction with standard tumor markers and imaging.

Patient Case

An otherwise healthy male in his mid 30s presented with a left testicular mass. Scrotal ultrasound demonstrated a 3.0 cm hypoechoic lesion within the left testis. He was taken to the operating room for a left radical orchiectomy. Final pathology revealed a 3.2 cm pure seminoma with lymphovascular invasion; surgical margins were negative. Serum tumor markers, including AFP and β-hCG, were within normal limits. Initial metastatic evaluation with contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis was unremarkable.

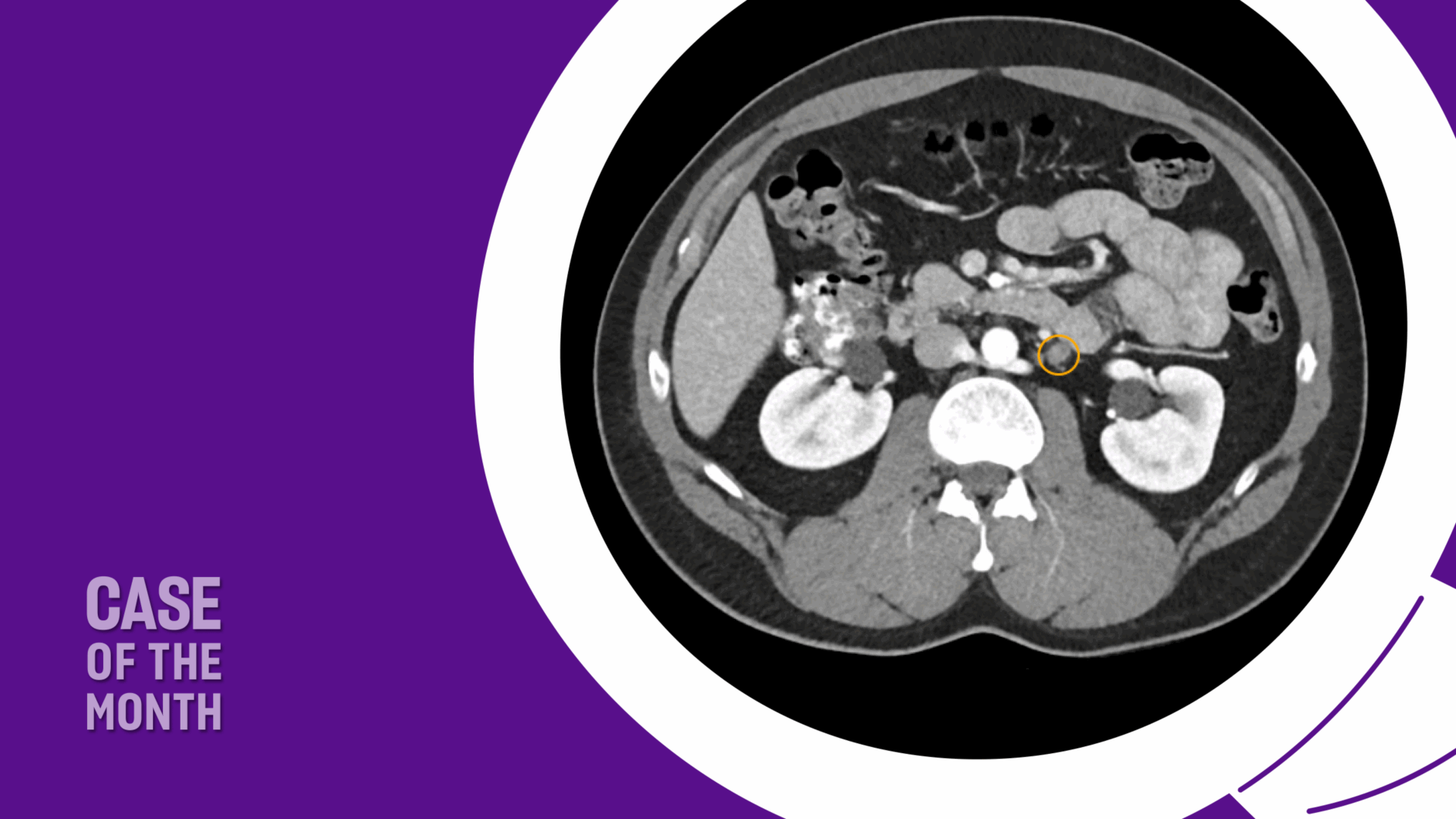

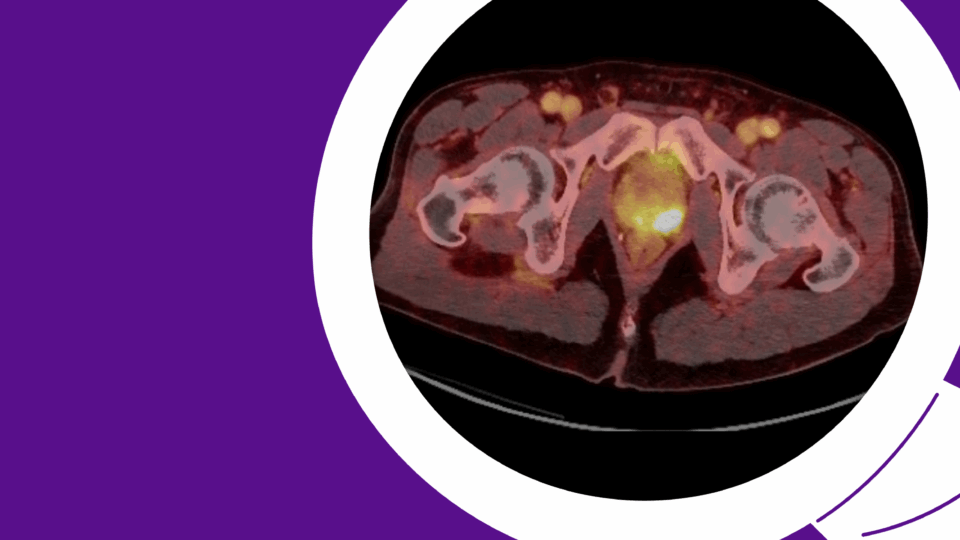

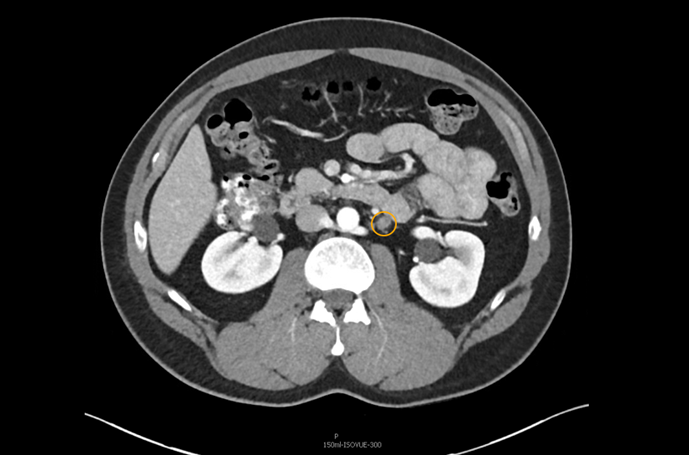

The patient was appropriately managed with active surveillance. Six months following orchiectomy, surveillance CT imaging demonstrated two enlarged para-aortic lymph nodes measuring 1.5 cm, consistent with metastatic disease (Figure 1). CT of the chest remained negative, and serum tumor markers continued to be within normal range.

Given his clinical stage IIA seminoma, treatment options including primary chemotherapy versus RPLND were discussed. The patient expressed a strong preference to avoid the long-term sequelae of systemic chemotherapy and elected to proceed with primary RPLND.

RPLND: Rationale for Its Role in Metastatic Seminoma

Testicular cancer is the most common malignancy in men aged 15 to 44 years. Germ cell tumors (GCTs) account for approximately 95 percent of cases and are broadly categorized as seminomatous or non-seminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCT). The retroperitoneum is the most common initial site of metastatic spread, and disease is classified as clinical stage (CS) IIA, IIB, or IIC based on the size and extent of retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy.

Historically, metastatic seminoma has been treated primarily with chemotherapy or radiation therapy. While long-term disease-specific survival exceeds 90 percent for CS IIA/B disease, increasing attention has been paid to the long-term morbidity associated with these treatments. Given the young age of most patients and their excellent cancer-specific outcomes, survivorship issues are particularly important.

Radiation therapy has been associated with acute toxicity and an increased risk of long-term cardiovascular complications, with major cardiac events reported in up to 19 percent of patients.1 Additionally, radiation therapy is associated with approximately a two-fold increased risk of secondary malignancies.2,3 Chemotherapy, while highly effective, carries risks of infertility, renal dysfunction, neurotoxicity, and ototoxicity.4 Furthermore, chemotherapy-treated patients have a three-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction compared to the general population. Large population-based studies involving over 110,000 survivors have demonstrated a relative risk of secondary malignancies ranging from 1.7 to 4.5 following chemotherapy and/or radiation.5 Notably, second primary malignancies have emerged as a leading cause of late mortality among testicular cancer survivors.6

In an effort to reduce treatment-related morbidity, contemporary management strategies have emphasized active surveillance for stage I disease, reduced radiation fields and doses, and risk-adapted chemotherapy regimens. In parallel, interest has grown in primary RPLND for select patients with stage II seminoma as a means of achieving disease control while minimizing long-term systemic toxicity.

RPLND offers diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic value. Historically, its use in seminoma was limited due to higher surgical morbidity, limited understanding of retroperitoneal neuroanatomy, and suboptimal perioperative care.7 Over the past several decades, advances in surgical technique, improved knowledge of lymphatic drainage patterns, nerve-sparing approaches, and standardized perioperative pathways have significantly reduced morbidity. These improvements have made RPLND an increasingly attractive option for carefully selected patients with early metastatic disease who wish to avoid chemotherapy or radiation.

RPLND: Clinical Trials

The safety and efficacy of primary RPLND for early-stage metastatic seminoma have been evaluated in several prospective trials and retrospective series (Table 1).

Table 1. Contemporary reports of primary RPLND for metastatic seminoma

| Study | N | Stage | Approach | Template | Follow-up | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEMS trial8 | 55 | IIA & IIB | Open | Modified | 24 mo | 18% |

| PRIMETEST trial9 | 31 | IIA & IIB | Open (42%) or Robotic (58%) | Modified | 36 mo | 31% |

| COTRIMS trial10 | 30 | IIA & IIB | Open (90%) or Robotic (10%) | Modified | 22 mo | 10% |

| Tachibana et al11 | 67 | IIA & IIB | Open | Modified 36 Bilateral 31 |

22 mo | 16.4% |

| Zeng et al12 | 104 | IIA & IIB | Open | Modified 36 Bilateral 68 |

29 mo | 18.3% |

Pooling data from prospective trials, two-year recurrence-free survival without adjuvant therapy ranges from approximately 70 to 90 percent. Importantly, we have identified that longer intervals between orchiectomy and RPLND appear to correlate with less aggressive tumor biology and lower recurrence risk. Based on these data, the American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines now recognize primary RPLND as a treatment option for select patients with stage II seminoma.

RPLND: Safety

Primary RPLND is associated with an acceptable safety profile. The 30-day complication rate was 11.9 percent, with most complications being low grade, including ileus and lymphocele formation.13 Implementation of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols has further reduced morbidity. Median length of stay has decreased to approximately three days, compared to historical reports of six days for primary RPLND.

Chylous ascites remains the most concerning complication, with a reported incidence of approximately 1.9 percent, comparable to rates observed in primary RPLND for NSGCT (0.2 to 2.1 percent).14

Patient Treatment and Outcomes

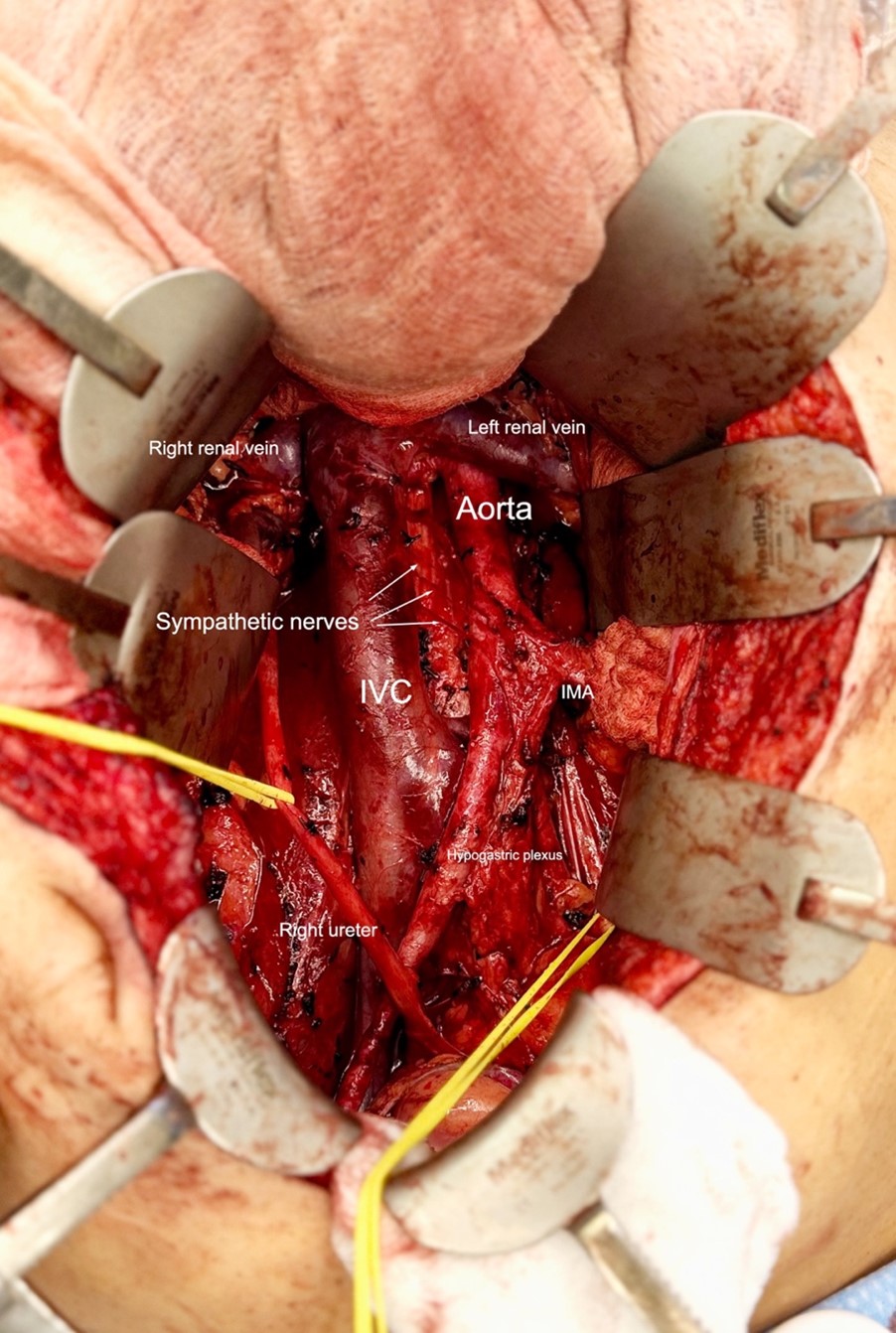

The patient underwent primary RPLND without complications. A bilateral dissection template with right nerve-sparing was performed (Figure 2). The procedure was completed through an upper midline incision, with an operative time of approximately five hours and an estimated blood loss of 100 mL.

Postoperatively, the patient was managed on an ERAS pathway. He was advanced to a clear liquid diet on postoperative day (POD) 1 and a low-fat diet on POD 2. He was discharged home on POD 2 with instructions to continue a low-fat diet for two weeks.

Final pathology revealed metastatic seminoma in 2 of 16 para-aortic lymph nodes, largest measuring 1.8 cm, consistent with pN1 disease. Interaortocaval and paracaval lymph nodes (32 nodes) were negative.

Given his limited nodal disease and preference to avoid chemotherapy, surveillance was recommended rather than adjuvant therapy. Follow-up included standard serum tumor markers and incorporation of tumor-informed circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) assays to enhance detection of microscopic disease, along with routine imaging.

At one-year follow-up, the patient remained without evidence of disease recurrence and had preserved normal ejaculatory function.

Conclusions

This case illustrates the evolving role of primary RPLND in the management of select patients with stage II seminoma.

In carefully chosen individuals with limited-volume retroperitoneal disease and normal tumor markers, primary RPLND can provide effective oncologic control while avoiding the long-term toxicities of chemotherapy or radiation. Advances in surgical technique, nerve-sparing approaches, and perioperative care have significantly reduced morbidity and preserved quality of life. As survivorship considerations become increasingly important in testicular cancer, primary RPLND should be part of shared decision-making discussions for appropriately selected patients, ideally within experienced centers.

References

- Hallemeier CL, et al. Urol Oncol. 2013;31(8):1832-1838. DOI.

- van Leeuwen FE, et al. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(3):415-424. DOI.

- Beyer J, et al. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(4):878-888. DOI.

- Fung C, et al. Adv Urol. 2018;2018:8671832. DOI.

- Haugnes HS, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(30):3752-3763. DOI.

- Travis LB, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(18):1354-1365. DOI.

- Masterson TA, Cary C, Foster RS. Urol Oncol. 2021;39(10):698-703. DOI.

- Daneshmand S, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(16):3009-3018. DOI.

- Hiester A, et al. Eur Urol. 2023;84(1):25-31. DOI.

- Heidenreich A, et al. Eur Urol Oncol. 2024;7(1):122-127. DOI.

- Tachibana I, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(23):3930-3938. DOI.

- Zeng J, et al. J Urol. 2025;213(6):753-765. DOI.

- Tachibana I, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(32):3762-3769. DOI.

- Cary C, Foster RS, Masterson TA. Urol Clin North Am. 2019;46(3):429-437. DOI.