Hydronephrosis is one of the most common urologic abnormalities we encounter in pediatric urology, most often caused by ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJO). While hydronephrosis is common, its extreme form—giant hydronephrosis—is a rare presentation. Just over 600 cases have been described in the literature, usually occurring in children or young adults, and UPJO remains the most frequent underlying cause.

This case of the month highlights one such rare presentation in a 13-year-old male. The patient was found to have a giant hydronephrotic left kidney—measuring 26.7 x 20.3 x 14 cm by CT—following blunt abdominal trauma resulting in hematuria. Given the massive size of his kidney and the lack of parenchyma, we performed a robotic left nephrectomy.

Case Highlights:

- The patient was diagnosed with congenital hydronephrosis as an infant but was lost to follow up.

- A robot-assisted left nephrectomy was performed through a small midline incision; partial intraoperative decompression was required.

- Pathology was consistent with UPJO, underscoring the importance of long-term follow up in patients with known hydronephrosis, even in the absence of early symptoms such as UTIs or pain.

Hydronephrosis and UPJO

Hydronephrosis is defined as dilation of the renal pelvis and/or calyces and is graded based on the severity of the dilation and its direct impact to the renal parenchyma.1 The higher the grade, the more likely the hydronephrosis is related to a pathologic condition, such as obstruction.

UPJO is the most common pathological cause of hydronephrosis in children and requires surgical intervention if it’s resulting in urinary tract infections, loss of renal function, flank/abdominal pain, kidney stone formation, or worsening dilation on follow up imaging. The most common causes of UPJO in children include intrinsic obstruction from an aperistaltic segment of the ureter resulting in poor outflow of urine, or extrinsic obstruction from a crossing vessel over the ureter.2

Giant hydronephrosis is variably defined as having more than one to two liters of urine in the collecting system.3 In addition to UPJO, other etiologies include chronic ureteral obstruction from stones or tumors in adults.4

Patient Case

The 13-year-old male had a history of asthma and was playing basketball when he was accidentally struck in the abdomen. Shortly afterwards, he developed gross hematuria and was taken to the emergency room.

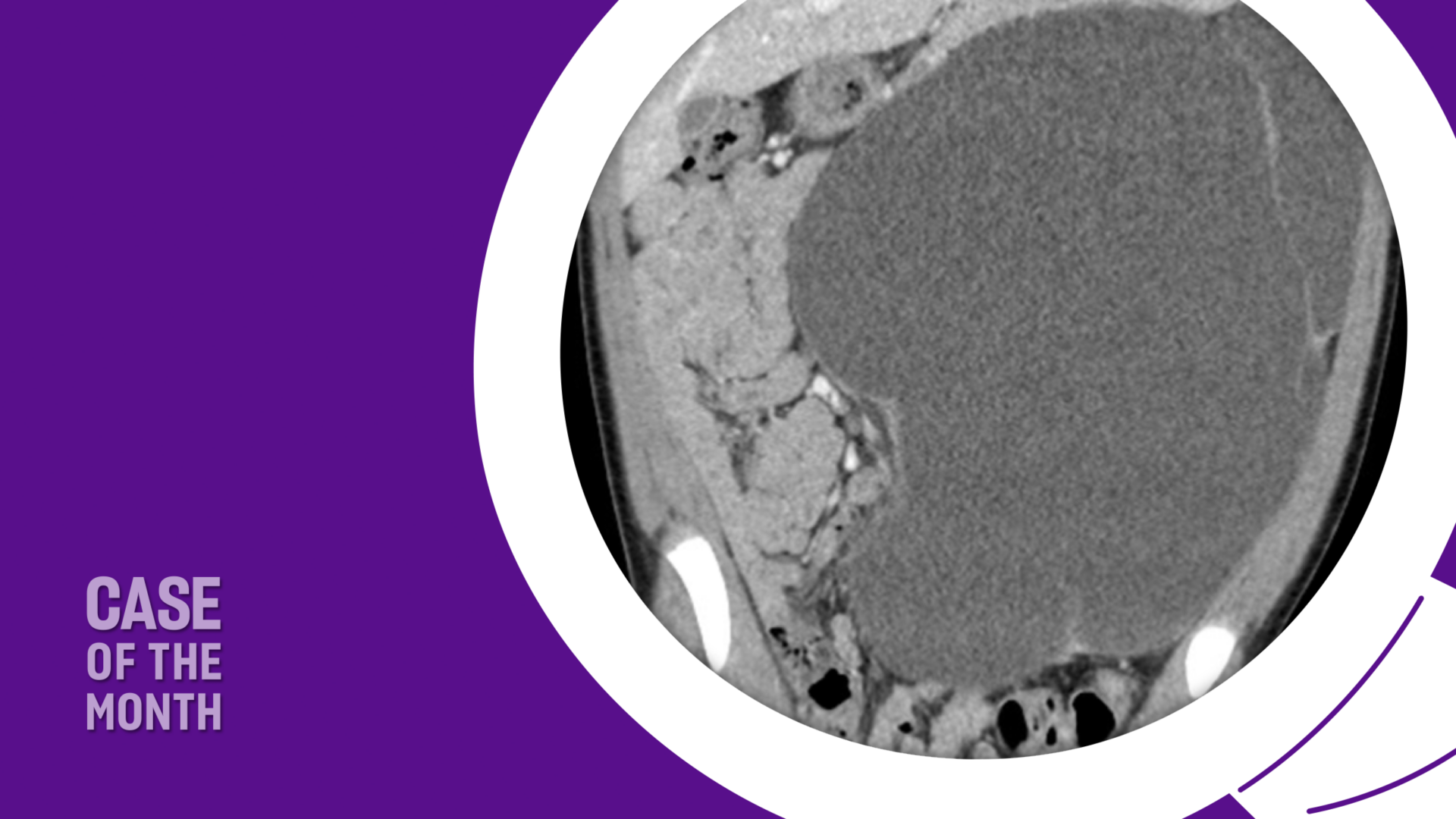

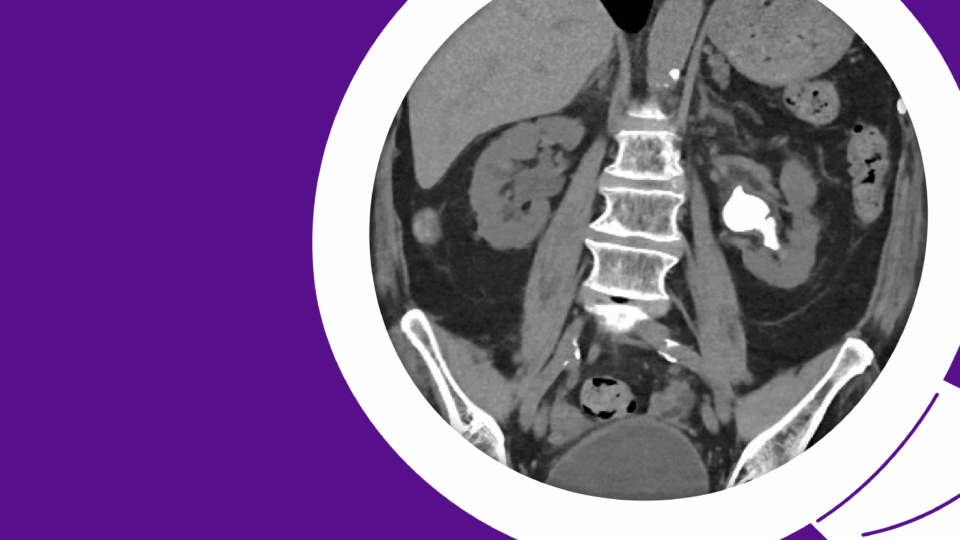

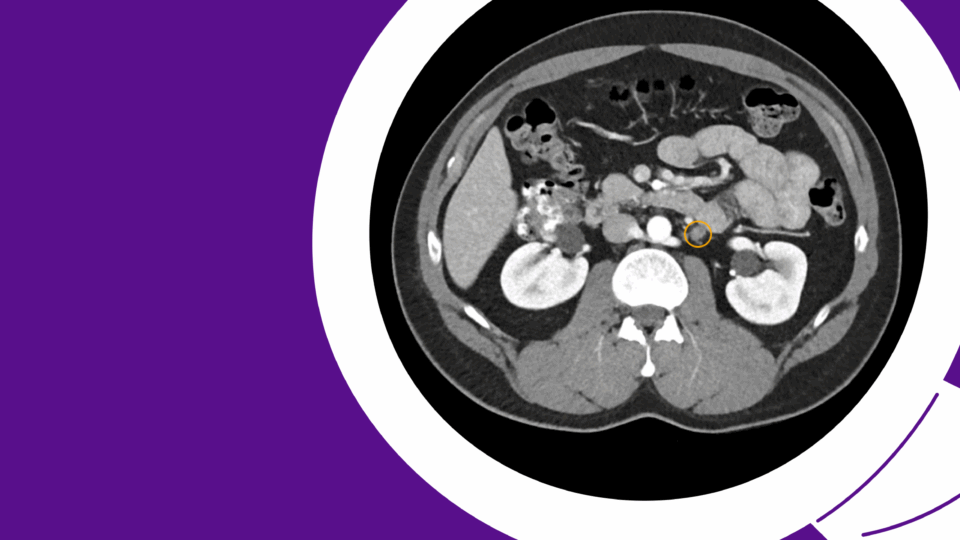

On physical exam, a large, nontender, left palpable mass was felt on his abdomen. A CT demonstrated a massive left hydronephrotic kidney measuring 26.7 x 20.3 x 14 cm with no visible renal parenchyma and displacement of the small and large bowel to the right side (Figure 1). Laboratory values showed a normal hemoglobin of 11.9 g/dL and a creatinine level of 0.6 mg/dL.

The mother indicated her son was born with congenital hydronephrosis but was lost to follow up as an infant. He never had issues with urinary tract infections, gross hematuria, or pain.

We discussed management options including decompression of the hydronephrotic kidney with either an external nephrostomy tube, internal ureteral stent, or nephrectomy. Given the appearance of no parenchyma and low likelihood of remaining function, a decision was made to perform a robotic left nephrectomy.

Robotic Nephrectomy

Initial robotic access to his abdomen was challenging due to limited intraperitoneal space. However, we were able to partially decompress the kidney intraoperatively in a controlled manner to safely perform the robotic nephrectomy, thus avoiding a large surgical incision.

Over three liters of urine was removed from the affected kidney. The patient did well and was discharged on postoperative day one with good pain control.

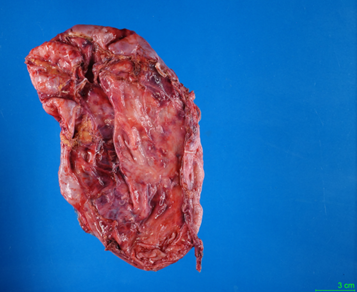

The final pathology demonstrated a 20.0 cm atrophic, decompressed kidney largely replaced by fibrosis with mild chronic nonspecific inflammatory infiltrate consistent with obstructive uropathy (Figure 2). The patient recovered well from surgery.

Discussion

At NYU Langone, this case of giant hydronephrosis presenting with gross hematuria following blunt trauma was successfully managed with a robotic approach. The kidney was decompressed intraoperatively and removed through a small midline incision, avoiding the need for a large open surgery.

The differential diagnosis for giant hydronephrosis should include intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal cysts, pseudomyxoma, ascites, renal tumor, pancreatic pseudocysts, retroperitoneal tumor, and ovarian cysts.5 It is often indolent, and some patients are asymptomatic. However, symptoms may include flank pain, chronic back pain, hematuria, protuberant abdominal mass, urinary tract infections, poor appetite, nausea, or vomiting.

Timely recognition and appropriate management are critical to prevent complications. This case illustrates how robotic surgery can offer a minimally invasive solution even in technically challenging cases.

References

- Nguyen HT, et al. J Pediatr Urol. 2014;10(6):982-998. DOI.

- Steinberg RL. UPJ obstruction – reconstructive urology. Urology Core Curriculum. American Urological Association. Accessed March 11, 2025. https://university.auanet.org/core/reconstructive-urology/reconstruction-of-upj-obstruction/index.cfm

- Stirling WC. J Urol. 1939;42(4):520-533. DOI.

- Budigi B, Dyer RB. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2019;44(5):1946-1948. DOI.

- Mountney J, Chapple CR, Johnson AG. Urol Int. 1998;61(2):121-123. DOI.