As long-term survival following treatment for muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) continues to improve, urogynecologists may more frequently encounter post-cystectomy prolapse. Therefore, it is crucial to understand treatment options and align them with a patient’s lifestyle and sexual health priorities.

In this Case of the Month, we describe a young, physically and sexually active patient with post-cystectomy prolapse who successfully underwent robotic sacrocolpopexy. The procedure carried risks due to her surgically distorted anatomy and anticipated peritoneal adhesions. But collaboration with reconstructive urology made for a safe and effective surgery, and the patient continues to experience symptomatic relief nearly four years later.

Below, we detail the procedure and why it was the best option. We also discuss the unique considerations of all available treatments, including vaginal pessaries, colpocleisis, and native tissue repair. We hope this case encourages other providers to consider that when sacrocolpopexy is the best option, a team-based approach can deliver success.

Case Highlights:

- A 53-year-old MIBC survivor with vaginal protrusion was dissatisfied with a vaginal pessary and sought surgical intervention.

- Sacrocolpopexy was elected due to its durability and the patient’s desire to maintain sexual function.

- Urogynecology and reconstructive urology performed a successful procedure, which required unique port placement to accommodate distorted anatomy and extensive enterolysis due to peritoneal adhesive disease.

- As bladder cancer survivorship improves, the prevalence of post-cystectomy prolapse may rise; understanding treatment options and their relative risks and benefits is paramount.

Background: Post-Cystectomy Prolapse

In the female patient, radical cystectomy for MIBC traditionally involves en bloc resection of the bladder, urethra, uterus, cervix, bilateral adnexa, and anterior vaginal wall. This results in an anterior vaginal defect, which is closed by mobilizing a portion of the posterior vagina to create a vascularized flap. While reproductive organ sparing (ROS) cystectomy has gained popularity for patients with clinically localized disease, it is not yet considered standard of care, and most urologic oncologists report they do not routinely perform ROS cystectomy, even in eligible patients.1

A necessary consequence of radical cystectomy is that crucial vaginal support structures are excised or disrupted including DeLancey’s level I and level II support (see DeLancey’s Three Levels of Support below).2 After their operation, patients therefore have only distal vaginal support, likely putting them at increased risk for the development of prolapse. Because prolapse in patients with a history of radical cystectomy is poorly reported in the literature, the true incidence is unknown, but may be as high as 23 percent.3,4

DeLancey’s Three Levels of Support

In 1992, Dr. John DeLancey described three distinct anatomic structures thought to be responsible for vaginal support.

- Level I includes the cardinal/uterosacral ligament complex and supports the vaginal apex.

- Level II supports the mid-vagina via the endopelvic fascia and its attachments to the lateral pelvic sidewalls at the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis.

- Level III provides distal vaginal support and is composed of vaginal attachments to the perineal membrane and perineal body.

Dr. DeLancey’s framework remains foundational to understanding the anatomic structures, whose failure may contribute to the development of pelvic organ prolapse.

Case Presentation

The 53-year-old patient presented to the urogynecology clinic in 2020 complaining of bothersome vaginal protrusion. She had a history of two pregnancies (both cesarean deliveries), was sexually active, and a former smoker (>30 pack years). In 2018, she was treated for MIBC with radical cystectomy/urethrectomy, hysterectomy, bilateral salpingectomy, flap vaginoplasty, and continent cutaneous urinary diversion (Indiana Pouch). She was initially fitted with a ring with support pessary but was unhappy with this method of symptom relief and desired surgical intervention.

The options for surgical management were reviewed in detail, with the understanding that outcomes data in this specific population are extremely sparse.

The patient worked a physically demanding job and wished to retain the capacity for vaginal intercourse, making her a poor candidate for native tissue repair and ineligible for obliterative repair such as colpocleisis. Vaginally placed mesh products, which would have allowed for prolapse repair without necessitating peritoneal access, had been removed from the market by the FDA one year before. Ultimately, mesh-based repair with sacrocolpopexy was selected for its improved durability; however, this approach carried known risks, particularly given her surgically distorted anatomy and anticipated peritoneal adhesive disease.

Robotic Sacrocolpopexy

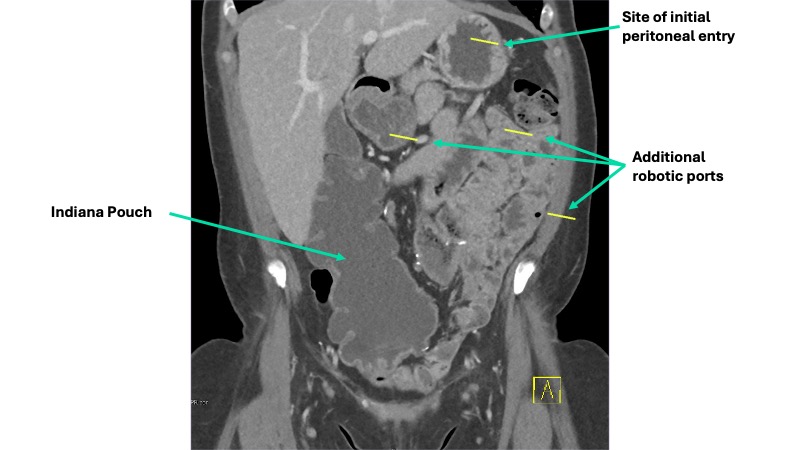

A multidisciplinary approach was planned. Urogynecology partnered with reconstructive urology, the service that had performed her continent cutaneous urinary diversion, in order to ensure safe peritoneal access and lysis of adhesions. She also had a known parastomal hernia, and concomitant repair was planned. Her Indiana Pouch, which was located on the right, occupied most of the right lower quadrant, requiring planned adjustments to robotic port placement (Figure 1).

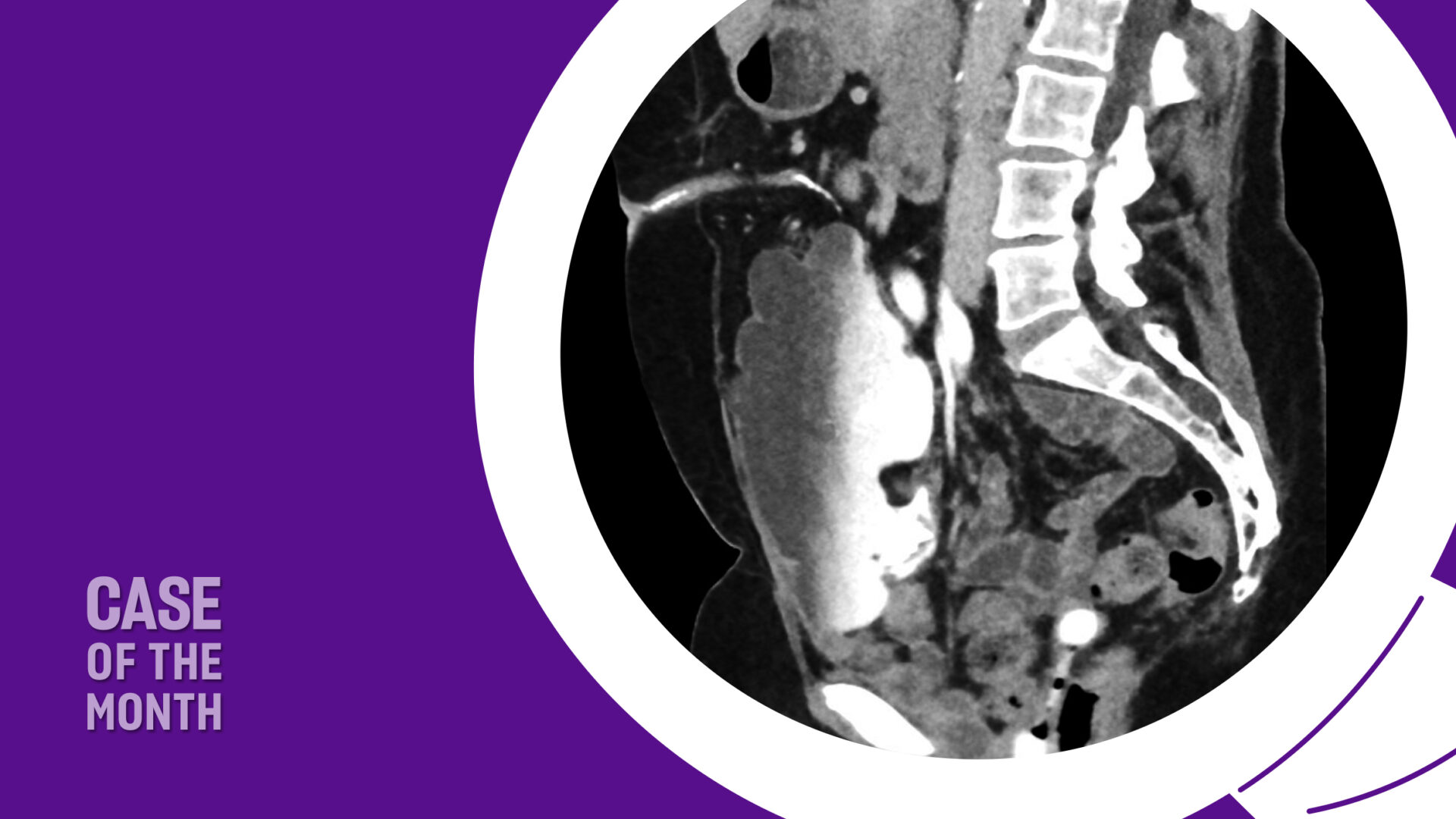

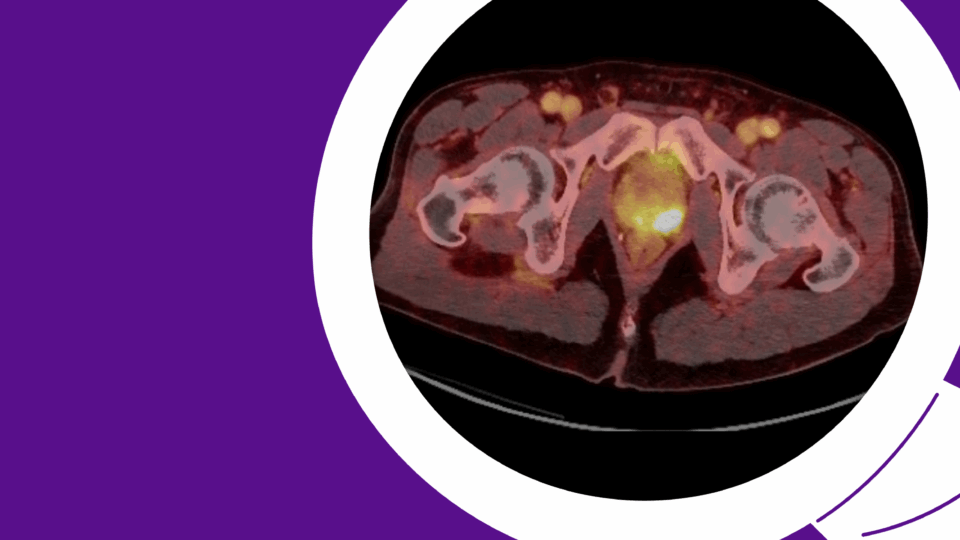

Sagittal imaging suggested the pouch would be adherent to the anterior abdominal wall and would therefore not impact sacral dissection or mesh placement along the right pelvic sidewall (Figure 2). Her stoma was located in the midline, at the umbilicus.

After induction of general anesthesia, a 14 French foley catheter was placed through the stoma to drain the neobladder intraoperatively. Peritoneal access was gained through an open approach at Palmer’s Point and allowed careful inspection of the peritoneal cavity, which revealed marked adhesive disease around the Indiana Pouch and throughout the anterior abdomen and pelvis. The sacral promontory and right pelvic sidewall were relatively spared. Additional robotic ports were placed a minimum of 8 cm from one another, all on the left side of the abdomen to avoid injury to the Indiana Pouch (Figure 1).

The reconstructive urology team performed extensive lysis of adhesions to mobilize the small bowel out of the pelvis, expose the vagina, and expose the stoma for parastomal hernia repair. The small bowel was so densely adherent to the vaginal apex that an intentional vaginotomy (colpotomy) was required, which was repaired with absorbable suture in two layers before mesh placement.

Anterior vaginal dissection was not required, given the absence of the bladder and urethra. The rectovaginal space was dissected in the usual fashion; this space was not significantly scarred. An ultra-lightweight Y-shaped polypropylene mesh was introduced and attached to the vagina with interrupted CV-2 Gore-Tex sutures. After dissection of the peritoneum and fibroadipose tissue from the presacral space, CV-2 Gore-Tex was used to suspend the mesh to the anterior longitudinal ligament overlying the upper third of the S1 vertebra.

Reperitonealization of the mesh was attempted in order to minimize the risk of further bowel adhesive disease. The sacral arm of the mesh was covered with peritoneum without difficulty. Given the prior radical anterior pelvic surgery, we were not able to sufficiently mobilize peritoneum to cover the vaginal portion of the mesh. A flap of fibroadipose tissue from the lower anterior abdominal wall was mobilized and used to cover the majority of the mesh. A surgical adhesion barrier was placed over the remaining exposed mesh.

The patient had an uneventful recovery and remains free from prolapse symptoms and without evidence of recurrent bladder cancer nearly four years later.

Discussion

In this case of post-cystectomy prolapse, the patient expressed dissatisfaction with a vaginal pessary and sought a surgical intervention that would have little impact on her sexual health. Sacrocolpopexy provided a durable treatment and was successfully performed using an interdisciplinary approach to address the altered anatomy.

The case illustrates why selecting an approach to treatment for pelvic organ prolapse in a patient with prior radical cystectomy requires an understanding of patient-specific risk factors, lifestyle, and symptom relief priorities. Data specific to this patient population is extremely limited, but virtually all treatment options have unique considerations.

Vaginal Pessaries: All patients with prolapse should be counseled about the safety and availability of vaginal pessaries for symptomatic relief, and those with a history of radical cystectomy are no exception. The two measurements most reliably associated with the ability to successfully use a vaginal pessary are the genital hiatus (GH) and the total vaginal length. Patients with a short vagina and wide GH will not be able to accommodate a pessary large enough so that it would not be at risk for expulsion during physical activity or Valsalva.5 Following radical cystectomy with flap vaginoplasty, the vaginal length or width may be restricted, such that successful pessary fitting is not possible. However, the likelihood of successful pessary fitting in this population has not been studied.

Colpocleisis: Obliterative prolapse repair with colpocleisis is a viable surgical option for patients with a history of radical cystectomy, but it is only appropriate for those who are certain they are not interested in future vaginally penetrative intercourse. Colpocleisis has extremely high success rates and does not require peritoneal entry, so it is therefore an excellent option for patients with complicated surgical abdomens. Long-term recurrence, patient satisfaction, and regret rates are favorable.6,7

Native Tissue Repair: Native tissue repair, such as the uterosacral ligament suspension and sacrospinous fixation, are plagued by high prolapse recurrence rates, and it stands to reason that durability may be further compromised following radical cystectomy due to the absence of pubocervical fascia.8 Vaginally placed mesh materials for repair of prolapse promised a more durable option for vaginal repair and have been performed with favorable outcomes in women with a history of radical cystectomy.9,10 However, studies of vaginal mesh for prolapse ultimately failed to demonstrate improved efficacy over native tissue repair, contributing to the FDA’s 2019 decision to halt all sales, distribution, and marketing of vaginal mesh for prolapse.11

Sacrocolpopexy: Sacrocolpopexy is, of course, potentially complicated by the risks associated with intraperitoneal surgery in a complicated surgical abdomen. Risks include injury to the neobladder, catheterizable channel, or transplanted ureters. There is also a risk of injury to small or large bowel or other intraperitoneal structures due to adhesive disease. However, sacrocolpopexy may present the most durable option for patients who wish to retain the ability for penetrative intercourse.12

In conclusion, treatment options for prolapse carry unique benefits and risks for this population and patients should be counseled that there is a paucity of safety and efficacy data to guide management. Ultimately, choice of prolapse treatment should be highly individualized based on an understanding of the patient’s anatomy and overall health priorities.

References

1. Gupta N, et al. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2023;21(4):e236-e241. DOI.

2. DeLancey JO. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(6 Pt 1):1717-1728. DOI.

3. Lipetskaia L, et al. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27(4):e501-e504. DOI.

4. Richter LA, et al. Urology. 2021;156:e20-e29. DOI.

5. Clemons JL, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(2):345-350. DOI.

6. FitzGerald MP, et al. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17(3):261-271. DOI.

7. Song X, et al. Menopause. 2016;23(6):621-625. DOI.

8. Jelovsek JE, et al. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1554-1565. DOI.

9. Graefe F, et al. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(8):1407-1409. DOI.

10. Kuwata T, et al. IJU Case Rep. 2022;5(5):389-392. DOI.

11. Urogynecologic surgical mesh implants. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/implants-and-prosthetics/urogynecologic-surgical-mesh-implants. Accessed 8/22/2024.

12. Lee D, et al. Curr Urol Rep. 2019;20(11):71. DOI.